Environmental Challenges

As a disruptor for more than 30 years, my vision has defied stereotypical views of Indigenous Peoples and I have effected change in the arts, television, philanthropy and business. Today, I represent First Nations in negotiating renewable energy and mining projects. This work has been challenging, as projects can accrue positive economic benefits for First Nations while causing inevitable environmental impacts for all.

Everyone is faced with the reality of climate change, and the environmental justice challenge is the new movement. Environmental justice has been defined as the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, colour, national origin or income with respect to the development, implementation and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations and policies. The privileged one per cent have been given access to exploit resources and accrue massive wealth while damaging our environment and climate.

I work with First Nations every day and witness a multitude of different attitudes and understandings. We, as Indigenous Peoples, recognize that we live in balance with nature. We codified these beliefs long before the Industrial Revolution, before unsustainable population growth, before capitalism and globalization and before oil became the single most important economic commodity. The Indigenous worldview is now more important than ever, given the rapid pace of the depletion of our life-sustaining resources.

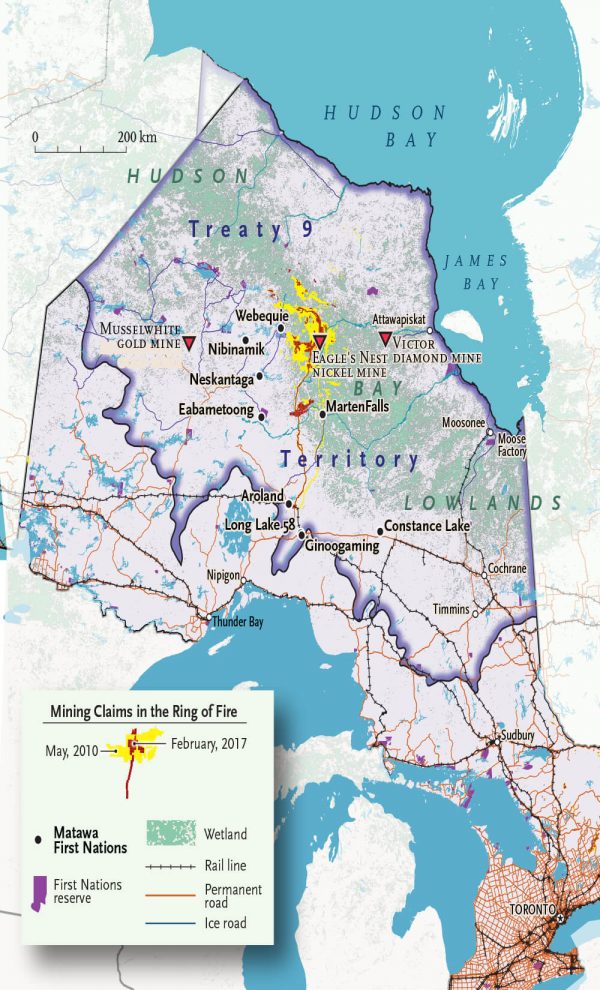

In the media, Indigenous groups appear to be anti-development. First Nations do oppose some projects and need to when all other means for justice become exhausted and when the negative impacts are understood to be too great. We are the ones who will directly suffer from polluted waterways and mercury-poisoned fish when projects disrupt traditional hunting grounds and culturally sensitive lands. I ask, should Indigenous Peoples and their codified values to prioritize the environment be given equal say when environmental policies are made? The answer is yes.

While we are not responsible for the environmental mess that exists today, we suffer from it equally and in some cases even more so. It’s only been in the last few years that Canadian courts have more seriously recognized our voice on environmental policy through the common law duty to consult and accommodate regarding resource development on or near our lands. Even with this obligation we have a limited voice, but it’s one that is growing stronger. The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples also acknowledges the right to free, prior and informed consent, which builds on this idea. Ultimately, the answer must come down to people working together to balance economic needs while staving off further environmental damage. But how do we devise a plan amidst the reality of environmental injustice, wherein Indigenous Peoples haven’t been active participants in free markets, private ownership or capitalism?

Everyone is faced with the reality of climate change, and the environmental justice challenge is the new movement.

Despite the need to decommission fossil fuels, many First Nations rely on gas and oil for funding. Many First Nations have no other means of securing revenues for their communities and so are forced to take oil and gas royalties. Certainly, we will continue to need fossil fuels in the short term, but we must develop a greater understanding of the energy mix that is required as we head toward a renewable energy future.

I have worked on the corporate side and have represented First Nations as a negotiator. I’ve had to come to terms with the fact that we’ve inherited a world where oil is the main commodity. Oil is the engine of the global economy, and wars have been fought over who controls it. Oil companies won’t go out of business overnight. As long as governments don’t have the courage or money, the transition away from the oil economy will remain difficult and elusive. In the short term, fossil fuels continue to play an important role whether we like it or not. The ultimate solution is to decommission fossil fuels while ramping up renewable energy.

The Indian Act has historically prevented access to capital for First Nations to develop streams of revenue that might result in our ability to develop, own and operate healthier renewable energy alternatives. First Nations require deeper capacity to negotiate a mixed energy supply that works for the environment while protecting the economy. While some First Nations still have concerns about developing wind and hydroelectric power, others have embraced them fully.

We need to advocate to curb consumerism and the idea of the continual growth machine. We need Indigenous leadership to fight for our rights, amending or repealing the Indian Act while holding fast to our Indigenous worldview. And we need a new plan to transition out of our dependency on fossil fuels.

The duty to consult and accommodate wasn’t given to us. We fought for it in the courts as a social justice issue. Now that we have this common law, government officials continue to find clever new ways of getting around it and continue to impose project approvals in and around our treaty lands, despite our opposition. This has to stop, and our fight will — and must — continue.

The only way to address environmental challenges is for Indigenous Peoples to become informed about the need to balance fossil fuels with renewable energy and to have a plan to decommission fossil fuels over time. We need to better understand the ever-changing conventions of environmental law, while concurrently fighting for our rights and justice.

Order now

from Amazon.ca or Chapters.Indigo.ca or contact your favourite bookseller or educational wholesaler