Fur Trade

Canada was built on the fur trade, which supplied European demand for pelts from animals such as the beaver (Castor canadensis) to make hats. In Michif, the word for beaver is “aen kaastor.” At the start of the fur trade, the First Nations did most of the trapping. However, the Métis, who are sometimes considered “children of the fur trade,” became skilled hunters and trappers as well. The Métis began making a living as trappers by the end of the 1700s. They sold furs to three fur trade companies: Hudson’s Bay Company, the North West Company, and the American Fur Company. Dealing with competing fur trade companies was profitable for Métis trappers because they could sell their furs to the highest bidder. However, these profits began to diminish in 1821 when HBC and the NWC merged, operating as a new entity under the retained HBC name. HBC’s new-found monopoly on the fur trade meant lower fur prices. Furthermore, in Europe, less expensive silk hats became more popular during the 1830s, causing beaver prices to continue to drop. Prices also dropped for the furs of other animals, and many Métis trappers who had become reliant on the fur trade had to do other things to support their families.

Métis women were integral to the fur trade. They were sought after as marriage partners for fur trade managers because of their kinship ties to local First Nations and Métis. Some English Métis women, known as “Country Born,” married high-ranking officials and became members of the “Red River aristocracy.” French Métis women were likely to marry fur trade labourers such as French-Canadian voyageurs. Their work was vitally important, as they provided food such as garden produce, berries, fish and game to the fur trade posts. They also made and sold hand-worked items such as sashes and quilts.

Dealing with competing fur trade companies was profitable for Métis trappers because they could sell their furs to the highest bidder.

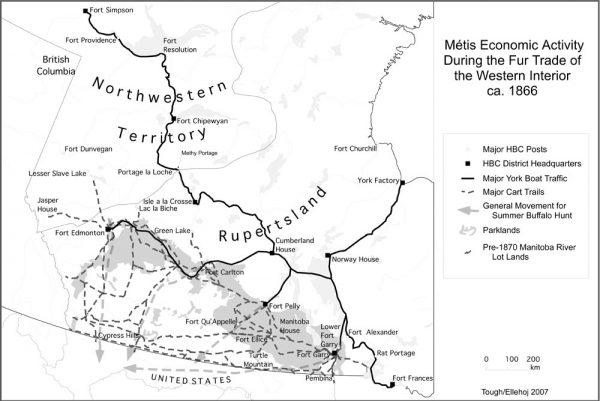

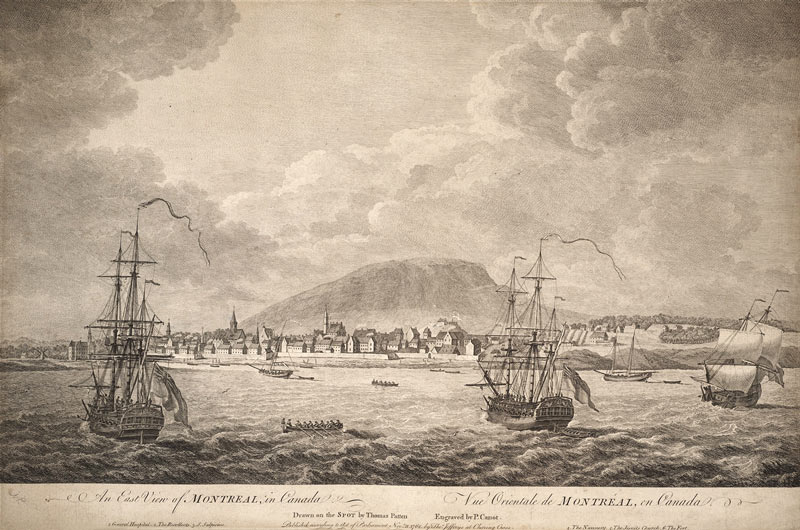

Voyageurs were the main labour force of the Montreal-based fur trade system. They paddled large fur trade canoes from Montreal to Fort William (now part of Thunder Bay, Ont.), then to what are now northern Alberta and the southern Northwest Territories and into present-day Oregon. Few roads made by people existed, making the rivers the best way of connecting communities. The voyageurs used the river systems to haul furs and goods for trading purposes.

From the 1770s until the 1821 merger, most voyageurs were French-Canadians from Lower Canada (now the southern portion of Quebec) and to a lesser extent Iroquois (Haudenosaunee) and Algonquins (Anishinaabeg). After the fur trade merger, the majority of boatmen working in the fur trade were Métis. Carrying on the voyageur way of life, they paddled transport canoes and York boats in the northern parts of the present-day Prairie provinces. They also unloaded freight canoes and York boats. Louis Riel counted on Métis boatmen, particularly the Portage La Loche brigade, as the muscle needed to support his provisional government during the Red River Resistance in 1869-70.

Métis boatmen worked for several months at a time, often enduring a great deal of hardship. In some places, a river would have too many rapids, or it was too narrow for boats to travel upon. Métis boatmen would then carry, or portage, their boats on their backs until they reached another lake or river. Those who were not carrying boats hauled heavy packs of trade goods on their backs. These bundles often weighed as much as 90 kilograms. This heavy weight was held in place by a strap or tumpline around their heads. They often carried their boats and heavy packs for several kilometres through tangled underbrush, over slippery rocks and through clouds of blackflies. Today, the Métis honour their ancestors by holding “Métis Voyageur Games” at events across Canada such as the Back to Batoche festival. These events test the strength, accuracy and endurance of the participants.

After the 1821 merger of HBC and the NWC, many Métis fur trade workers became free traders, independent hunters and trappers. The bison hunts took on an increased importance as demand for bison robes and hides — the leather was used to make industrial belts — became more prominent from the 1840s until the great herds of bison began disappearing in the 1870s. Some of the Métis served as fur trade provisioners and as hunters, providing processed bison meat or pemmican to the fur trade workers.

Many sons of HBC traders also became fur trade employees, serving in a variety of positions such as clerks, postmen and factors. These English Metis were less likely to be involved in labouring positions such as manning York boats than their French Métis compatriots.

Today, Métis in the northern parts of the Prairie provinces and in Northwest Territories continue to trap. The Métis continue to honour the traditions of their fur trade ancestors by holding annual “King Trapper” events.

Order now

from Amazon.ca or Chapters.Indigo.ca or contact your favourite bookseller or educational wholesaler