Oral Tradition

The Métis, like other Indigenous peoples, pass their histories, legends and family remembrances down through the Oral Tradition. Throughout the Métis Nation Homeland, the intergenerational transmission of culture occurred through the Oral Tradition, usually through Elders or the “Old People” as they are traditionally known.

Probably the best known aspect of the Oral Tradition is the telling of stories.

All traditional Indigenous stories, including Métis ones, generally have non-linear narratives and, unlike European stories, many of them have no real beginning, middle or end. Métis stories are often ongoing and can be carried over through time. The stories are layered and have multiple meanings, so people of varying ages will be left with different interpretations. Valuable life lessons are taught in the Métis Oral Tradition. For instance, a story about gluttony may be told through a humorous Wiisakaychak (trickster) story.

The Métis Oral Tradition is rooted in spirituality. Creation stories of how things came to be are usually told as trickster stories. Roogaroo (werewolf) or li Jiyaab (the Devil) stories are told so children do not forget their spiritual obligations to the Creator.

Traditional Indigenous cosmologies are kept alive through the telling of these stories. The Métis Oral Tradition has retained a spiritual aspect from its Algonquian ancestral cultures — Cree and Ojibwa — through these stories. In addition, traditional prayers and the giving of thanks in Métis heritage languages are handed down to families and are told only on very specific occasions. Some narratives in the Oral Tradition are considered sacred and are told only at certain times, and only to specific people.

The stories are layered and have multiple meanings…

The Métis Oral Tradition has been important in delineating kinship networks and genealogies. Before printed genealogies, this body of family knowledge and kinship connections prevented close relatives from marrying. Keeping an oral record of all the families and community relations was usually a task given to older women. This information was also useful because it outlined the trapping, fishing, hunting and plant harvesting grounds for medicine of various families.

Over the generations, the Oral Tradition has been vitally important in ensuring the survival of families. For instance, narratives in the Oral Tradition taught where food was located, how to harvest it, and how to prepare and eat it. This knowledge could be as diverse as where to dig for wild turnips (“navoos” in Michif) or the best time to hunt game animals. The Oral Tradition was also integral in maintaining Métis identity and group cohesion. In particular, stories relating to bison hunting, the Battle of Seven Oaks (1816), and the Battle of Grand Coteau (1851) connected listeners to their ancestors’ efforts to maintain their status as a self-sufficient, independent Indigenous nation.

The Métis Oral Tradition continues today in our print-based society, with stories being adapted into novels, poetry, art and film. Of course, Métis people still tell stories and pass along teachings through the Oral Tradition. Traditional knowledge within the Métis community has never been fully catalogued and continues its intergenerational transmission through oral expression, although this process has been greatly disrupted by societal pressures and forced assimilation policies such as residential schools and the Sixties Scoop.

Métis Stories

Métis stories — lii koont and lii atayoohkaywin (legends and fairy tales) and lii zistwayr (stories) — seamlessly blend Cree, Ojibwa and French-Canadian traditions. These two different spheres — a rural French/Catholic one and a Woodlands/Plains Algonquian one — have been fused into one Métis storytelling tradition. However, while Métis stories clearly derive from these traditions, they have different meanings, they have evolved to meet Métis needs, and they express a distinct Métis worldview.

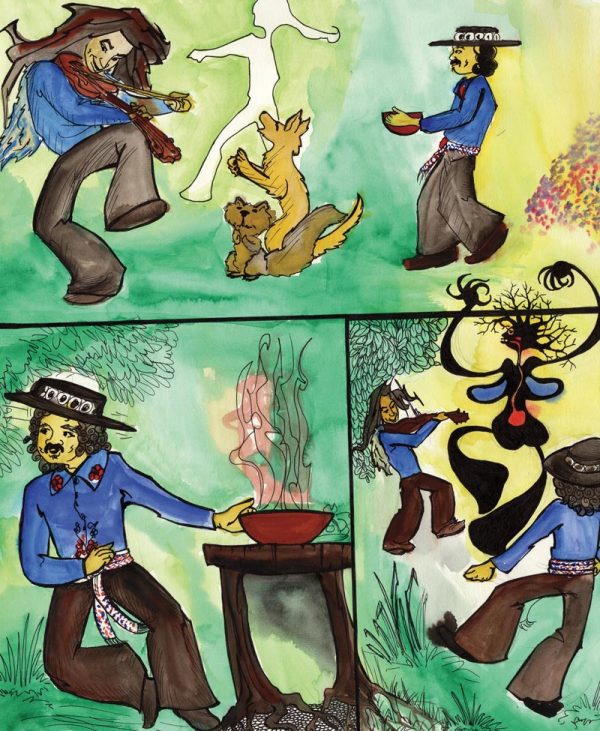

Traditional Métis stories include narratives about malevolent spirits that transgress against the Creator and society, as well as trickster-based creation or morality stories. Trickster stories are often humorous. These are generally creation stories and closely follow the oral narratives in the Cree and Ojibwa languages. The Métis tricksters — Wiisakaychak, Nanabush, and Chi-Jean — are essentially good characters who have very human foibles, including gluttony and selfishness. They serve as the Creator’s intermediaries to humans, and their adventures explain the workings of the natural environment. There are also stories about magical little people (li p’tchi mound or ma-ma-kwa-se-sak), lake monsters, the boogeyman or boogeywoman (Kookoush and La Veille de la Carême), the northern lights (lii chiraan), tall tales and fairy tales.

Métis stories grow darker with li Jiyaab (the Devil), li Roogaroo, Whiitigo, and Paakuk. The Métis werewolf, the Roogaroo, emerged from two traditions: the French-Canadian werewolf (loup-garou) and the Cree shape-shifter. Roogaroos can turn into black dogs, pigs, horses and bears, and are usually bad people who turn their backs on God. Roogaroo stories were told to ensure that youth behaved themselves, particularly during Lent. Whiitigos and Paakuks, Pakahk or Pakakosh are malevolent beings. Whiitigos, also known as Wehitigos, Whitakos or Windigos, are giant cannibalistic monsters with skeleton bodies and monstrous white heads. Also known in Michif as “Kaamoowachik” (cannibal spirit), they represent the omnipresent danger of starvation in hunting and gathering cultures. There can also be human Whiitigos — people who do bad things and are possessed by a malevolent spirit. Paakuks/Pakahks/Pakakoshs are emaciated flying skeletons that represent disease. During lonely evenings, they delight in spooking unsuspecting people with their demonic laughter.

In many traditional Métis stories there is a Catholic component, as shown with the characters li Jiyaab (the Devil) and li Roogaroo. Li Jiyaab can manifest himself upon unsuspecting people as a tall handsome stranger who visits country dances and mesmerizes all the young women with his mysteriousness, impeccable dress and good looks. The black dog is also considered a Roogaroo by many Métis storytellers. Li Jiyaab can trick people to steal souls or he can play simple tricks such as spoiling milk. This interpretation of the Devil is a mix of Catholic doctrine and folk Catholicism that sees the Devil as a bad-mannered trickster.

Métis stories are not “make-believe.” They are an integral component of the Métis worldview. The Elders or Old People, moreover, believe them to be true. Stories also have an undercurrent of truth and shouldn’t be easily dismissed as myth or superstition. Finally, stories are important to the Métis storytellers because they connect the storyteller to their Elders, ancestors and language. A word of caution should be noted to all those interested in Métis stories: they should be treated with respect. The Elder or storyteller who is sharing the story is doing so for a specific reason and not just for entertainment purposes. If you retell a Métis story, you must obtain the permission from the storyteller who told it to you. Not obtaining permission is a grave offence.

Order now

from Amazon.ca or Chapters.Indigo.ca or contact your favourite bookseller or educational wholesaler