Redress and Healing

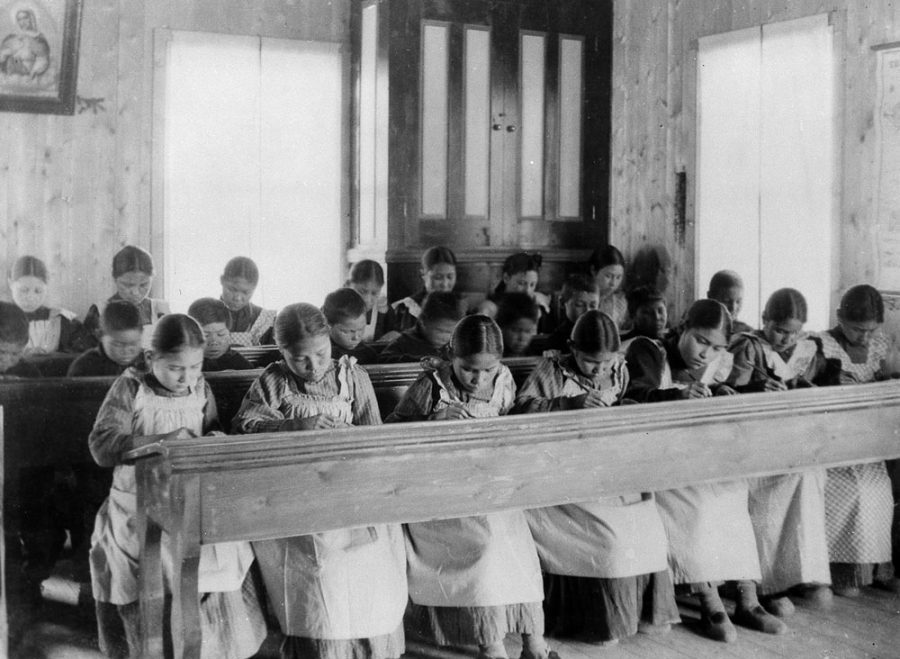

The term “Survivors” is now often used to describe the tens of thousands of people who attended residential schools in Canada, and lived to talk about it. One reason for using this term is to acknowledge the number of students who never made it home from residential schools. Another reason is to legitimize the experiences the students had while at residential schools, since the assault on their minds, bodies, cultures, languages, families and identities was often severe, long-lasting and of permanent effect. Survivors have spoken out for decades in their quest for recognition, healing and justice, demanding the government and country recognize what they were forced to endure. As a result, Survivors are at the heart of the broad efforts of truth and reconciliation now underway in this country. It is their collective cry for healing that is forcing this country to face its own past and to take responsibility for the harm inflicted on Indigenous Peoples, communities, nations and cultures.

While the general public is only now becoming aware of the truth about residential schools, Survivors have been coming forward since the 1960s. Throughout the latter half of the 20th century, Survivors began telling stories about their childhoods at residential schools in the form of memoirs, novels, songs and poetry, and through visual art like sculpture. During this time, the stories were neither heard nor acknowledged by the public at large — and if they were heard, they were not believed.

It took several decades for the general public in Canada to recognize these stories as truth, and to believe members of the church were abusing young children in their communities. In some cases, Survivors describe situations where even their own parents did not believe what was occurring in the schools. The schools and general societal divisions between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people were highly effective at keeping the abuse and suffering of the students out of the eyes and ears of mainstream Canada. Survivors of residential schools often met in groups to trade stories, whether it was at school reunions, around kitchen tables, in community halls or in band offices. Through the late 1980s and into the 1990s, many groups banded together to bring lawsuits against church and government institutions that inflicted harm upon them while in the schools.

Nora Bernard, a Survivor of the Shubenacadie Residential School in Nova Scotia, started meeting fellow Survivors around her kitchen table in Dartmouth, N.S., in 1987. In 1995, the group formed an association, and by 1998, it had grown to include 900 members from across Canada. This group helped spur a movement to get recognition and compensation for Survivors — a movement that soon joined with leaders from First Nations and Inuit organizations. In 2006, following years of litigation and other compensation efforts, nearly 100 church entities, the federal government, lawyers representing Survivors, the Assembly of First Nations and the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami agreed to settle litigation with the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement. It was the largest class-action settlement in Canadian history. Bernard, who died tragically a year after the agreement was reached, was posthumously issued the Order of Nova Scotia in 2008 for her tireless and life-changing work on reconciliation.

The settlement agreement created healing, compensation and commemoration initiatives in addition to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. By 2017, more than 38,000 claims for serious sexual and physical abuse were received through the Independent Assessment Process, while more than 80,000 Survivors received common experience payment recognizing the inherent harm inflicted on Survivors for simply having attended a residential school.

Another Survivor, former National Chief of the Assembly of First Nations Phil Fontaine, spoke publicly in 1990 about the physical and sexual abuse he experienced at the Fort Alexander Residential School in Manitoba. Though his testimony shocked many mainstream Canadians, his brave public disclosure paved the way for thousands of other Survivors to share their own experiences. As public knowledge and media coverage on residential schools grew, Survivors felt increasingly safe to share their stories. Despite this emerging ability to share, the pain experienced by Survivors in sharing cannot be underestimated.

In 1998, the Aboriginal Healing Foundation was established after recommendations from the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples and the 1998 statement of reconciliation given by the minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development. The foundation was initially allocated a grant of $350 million, to be used towards community-based healing programs for First Nations, Métis and Inuit Survivors of residential schools. Each community had distinct programming, often rooted in traditional healing practices and ceremonies, and created to best fit the needs of each region. In 2007, additional funding of $125 million was added to the Aboriginal Healing Foundation as part of the settlement agreement. In 2014, despite the early stages of healing in many areas of the county, funding for the AHF was not renewed by the federal government, and by 2015, the Aboriginal Healing Foundation ceased to exist.

Indigenous-led healing practices that draw on the teachings, cultural practices and worldviews of First Nations, Métis and Inuit peoples are crucial for Survivors, intergenerational Survivors and communities to heal. Recognition of the multiple forms of harm inflicted on Indigenous Peoples through the residential schools and other aspects of the aggressive assimilation policies of Canada is central in the path moving forward. Healing practices must take into account the emotional, physical, spiritual and mental harm inflicted upon communities and children inside the residential schools. Fundamentally, there must be full acknowledgment of the devastating impacts of early childhood trauma on individuals and communities. Sadly, early childhood trauma is something that takes a lifetime of healing to manage — a healing journey that needs to be met on a daily basis.

There also must be the recognition that the current state of Indigenous health across Canada is a direct result of the residential schools and aggressive assimilation policies of Canada. Repairing the complicated damage inflicted within and between families and restoring a sense of healthy community and family life in accordance with Indigenous principles and practices is also at the heart of this healing journey.

Reconnecting relationships with the land, with language and with other forms of cultural practice are deeply integrated into the healing journey for Indigenous Peoples and Survivors.

There remains a lot of healing to be done. It will take generations to fully heal from the damage inflicted. Ongoing investments to support truth-telling, cultural revitalization, trauma counselling and traditional healing practice, and to heal the physical harms created by the long-standing aggressive assimilation of Indigenous Peoples will be a critical element of our national healing work.

Order now

from Amazon.ca or Chapters.Indigo.ca or contact your favourite bookseller or educational wholesaler