Rivers, Lakes and Water Resources

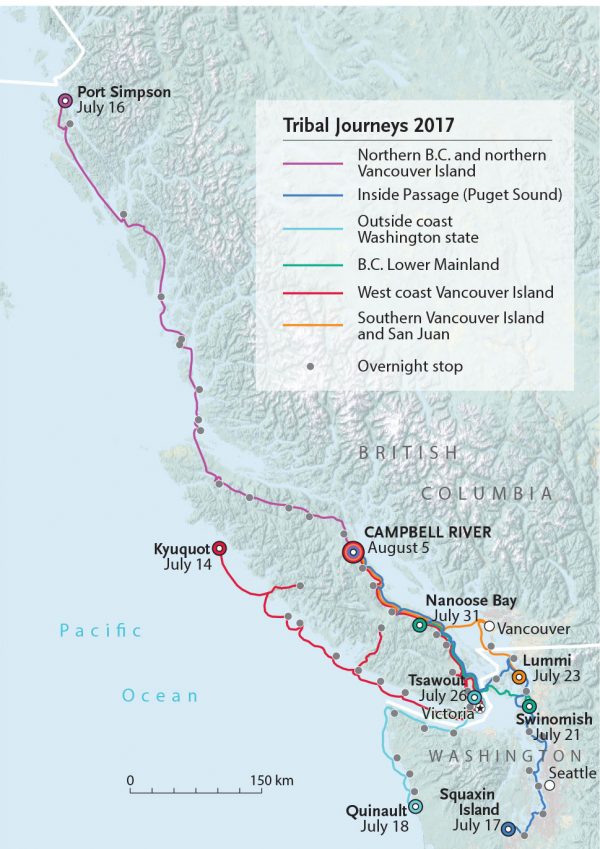

On August 5, 2017, 87 CANOES, each holding about a dozen pullers, traversed the rushing waters of Discovery Passage, where the Strait of Georgia bottlenecks between We Wai Kai territory on Quadra Island and Wei Wai Kum territory in Campbell River before gushing northwest into Johnstone Strait. Smoke from wildfires raging on the British Columbia mainland billowed over the coastal mountains and across the Salish Sea to Vancouver Island, shrouding the summer sun in a metallic blue-grey haze. Fumes, one of many summer signals of a rapidly warming planet, reminded swift seas of their inherent fragility before curling up to infiltrate the atmosphere.

The canoes, each distinguished by a unique chiselled silhouette and painted hull, pulled focus in this muted land and seascape. Skippers standing in the back of each vessel beached their watercraft, bringing canoes to rest gunwale to gunwale at Tyee Spit. Crews broke into the paddle songs of their respective canoe families, celebrating the joy of long-anticipated arrival on these Lekwitok shores.

Welcome to the Tribal Canoe Journey, an annual transnational Indigenous voyage and gathering that brings together communities throughout the Pacific Northwest. Every year, traditional ocean-going canoes depart from home ports as far flung as Haida Gwaii, B.C., and Grand Ronde, Ore. Their crews paddle for days and even weeks across hundreds of kilometres of coastline before arriving at that year’s host community for a week of potlatch singing, dancing, feasting and giveaways.

A regal Wei Wai Kum delegation, led by artist Jonathan Henderson and council member Curtis Wilson wearing their finest Chilkat blankets and thunderbird headdresses, received the canoes at Tyee Spit, the final port of call for the 2017 Tribal Canoe Journey. It felt like something powerful, even earthshaking, was happening. Most days, Discovery Passage serves as a shipping lane — just another maritime link in the global supply chain. But on that day, canoes forged ahead at the vanguard of Indigenous resurgence, piercing through a canvas painted in an eerie wash of environmental vulnerability. The scene was surreal.

With each canoe journey, Indigenous communities pull themselves towards greater cultural, social and political power.

More than 3,000 took in the pageantry at Tyee Spit that day — James Quatell, Quageelagee hereditary chief of the Wei Wai Kum Nation, among them. His family’s proud Kweladzatse big house ruled these shores for decades — perhaps centuries — until it was torn down in 1955, its fate the same as countless others destroyed by colonialism. “They couldn’t fully delete that from our people — but they tried,” Quatell intoned. “[The canoes’ arrival] was like a reawakening to something that was always there.”

That evening, our Wei Wai Kum and We Wai Kai hosts treated the Indigenous sojourners resting on their territories to a feast. There were so many guests that they ran out of salmon to fill bellies — a potlatch faux pas. The traditional Indigenous economy here in the Pacific Northwest is rooted in massive giveaways of art, goods and foodstuffs through a ceremony known as the potlatch. It is no small thing to let guests go hungry. For a community like Wei Wai Kum — for many generations rich on the bounty of the sea, this was a new and likely humbling experience. The salmon, lynchpin of life in the Pacific Northwest, is struggling. As smoke from the interior rolled over coastal mountains, below water the salmon’s decline on this once bountiful coast rends a fissure in the ecosystem where this keystone species once swam strong.

These existential environmental and human crises jolt Indigenous communities with urgent purpose. After supper, the host Wei Wai Kum and We Wai Kai invited all their guests into the fine Thunderbird Hall big house to witness the legendary Kwakwaka’wakw Red Cedar Bark ceremony. The whole community participated — men and women, young and old, worldly and supernatural — celebrating our enduring strength. Perhaps they danced just a little bit harder for the salmon, sang just a little bit louder for the air, and prayed just a little bit longer for the water.

These ceremonies were almost permanently erased from our communal memories as our presence was almost irrevocably effaced from these lands. By the turn of the last century, devastating diseases and bloody wars had cut our population by more than half, and perhaps even more than 90 per cent, although the exact numbers aren’t known. Entire villages and even some nations went extinct. Through programmatic dispossession, our land, water, and resource bases were taken from us almost completely. Today, First Nations’ reserve lands make up a paltry 0.4 per cent of British Columbia’s total landmass. In addition, generations of our children were abducted and incarcerated in residential schools. Their languages and cultures were literally beaten out of them in a systematic effort to “kill the Indian in the child.” At the same time, Indigenous cultural and spiritual gatherings were outlawed under the potlatch ban, which remained in effect until 1951. Most residential schools remained open until the 1960s and 1970s. The last closed in 1996. Against this history, which the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada describes as a “cultural genocide,” Indigenous communities are returning to strength by returning to enduring values and traditions. In the Pacific Northwest, the canoe journey is central to this resurgence.

Frank Brown, Heiltsuk from Bella Bella, organized the first canoe journey as part of Expo 86, the world’s fair in Vancouver that coincided with the city’s centennial. In 1984, Brown, then a college student working at the Vancouver Aboriginal Friendship Centre Society, received a request from the city’s mayor for Native participation in the exposition. Brown jumped at the opportunity. “My interest was to represent ourselves, to show the first form of transportation and communications on the coast,” Brown told me, “And for us, that was the glwa, or ocean-going canoe.” Post Expo 86, the idea continued to spread. In 1989, the late Emmett Oliver of the Quinault Nation organized the Paddle to Seattle to ensure Native representation in Washington state’s centennial. In 1993, Brown’s home community of Bella Bella hosted the first annual Qatuwas, or “people gathering together,” in conjunction with the United Nation’s International Year of the World’s Indigenous People. The gathering, thereafter known as the Tribal Canoe Journey, has been held every year since.

The people of the coast have embraced the vessel as an empowering tool in our process of decolonization. It really was a powerful vessel for community empowerment, youth development, cultural revitalization, language retention, and culture and protocol because you have to have those ceremonies intact when you exercise that ancient protocol of reconnecting with each other as canoe nations.

Frank Brown, Heiltsuk from Bella Bella

With each canoe journey, Indigenous communities pull themselves towards greater cultural, social and political power. In the Pacific Northwest and around the world, these communities are re-emerging from the desperate dark depths of colonization and taking centre stage in national and global fights for social and environmental justice. Paddling their formidable ocean-going canoes, these Indigenous protagonists may yet repaint the global canvas.

“I think that our people have an opportunity to not only share these important lessons within our own community about the sustainability of community, but also the sustainability of what communities depend upon for their sustenance and their very existence — and that

is the natural resources that really matter to us,” Brown told me. “We have to be able to look back in order to move forward.”

Order now

from Amazon.ca or Chapters.Indigo.ca or contact your favourite bookseller or educational wholesaler