Road Allowance People

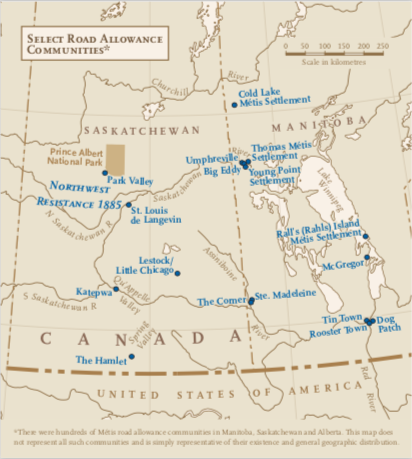

The Road Allowance period (roughly 1900-1960) is a key but little known element of Métis history and identity. As immigrant farmers took up land in the Prairie provinces after the 1885 Northwest Resistance, many Métis dispersed to parkland and forested regions, while others squatted on Crown land used — or intended — for the creation of roads in rural areas or on other marginal pieces of land. As a result, the Métis began to be called the “road allowance people,” and they settled in dozens of makeshift communities throughout the three Prairie provinces, such as Saskatchewan’s Spring Valley along the fringes of Prince Albert National Park, Chicago Line or “Little Chicago” in the Qu’Appelle Valley, and Manitoba’s Ste. Madeleine and Rooster Town (Winnipeg). Road allowance houses reflected the Métis’ extreme poverty — houses were usually uninsulated, roofed with tarpaper and built from discarded lumber or logs and various “recycled” materials. These small one- or two-room dwellings housed entire families.

As immigrant farmers took up land in the Prairie provinces after the 1885 Northwest Resistance, many Métis dispersed to parkland and forested regions, while others squatted on Crown land…

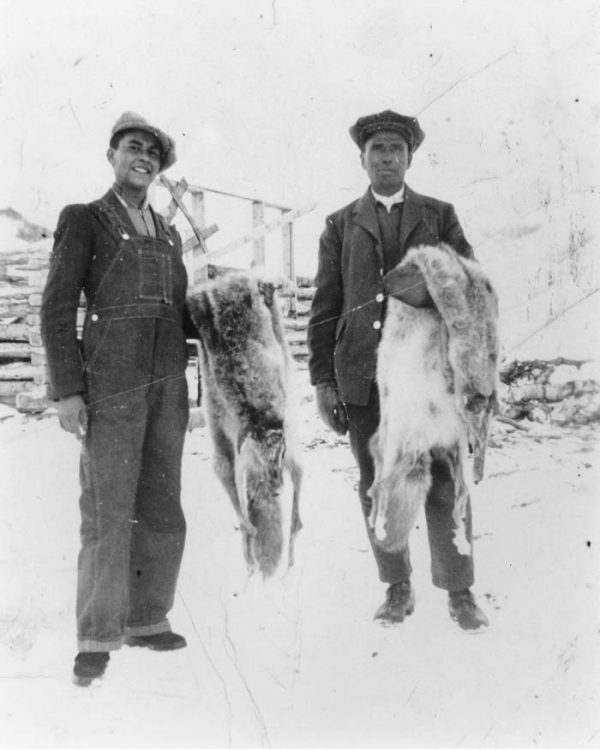

Road allowance communities popped up in areas where there was temporary employment. The Métis worked for farmers picking rocks and roots, clearing trees, and doing other labour jobs. They were paid minimal wages or were paid with bits of food such as chicken, pork, or beef. As a result, they could not afford to buy their own homes or pay rent. “Squatting” on Crown land was one way of providing a home for the family. To supplement their meagre income, many road allowance families picked Seneca root and sold it by the pound. They also picked berries, grew gardens, trapped and hunted game. Unfortunately, by 1939, laws were put in place making it illegal to hunt and trap out of season or without a licence. Many Métis went to jail or had to pay expensive fines for hunting out of season. In many cases, the animals they were hunting were their only source of food.

The road allowance Métis had a much lower standard of living than nearby Euro-Settlers. This poverty occurred well into the mid-20th century. As hunting and fishing regulations increased and government work projects failed, more Métis turned to government aid or “relief” to support themselves. Moreover, the Métis lived in a racist settler society that socially marginalized them, creating a myriad of social problems including poor health, low self-esteem, and a lack of viable employment opportunities. Road allowance Métis also lacked educational opportunities because children were not allowed to go to school if their parents didn’t pay property taxes. As a result, three generations of Métis were unable to receive a basic education. Those road allowance children who were allowed to attend schools were often teased and bullied about their customs, clothing, languages and food.

During the Depression, growing public pressure to deal with the “Métis problem” forced governments in the Prairie provinces to act. As a result, in the 1930s and 1940s the Alberta and Saskatchewan governments began to address the economic, social, and political marginalization of the road allowance people. Métis leaders in Alberta, such as Malcolm Norris, James Brady (better known as Jim Brady), and Peter Tomkins, convinced the Alberta government to enact the Métis Population Betterment Act in 1938, creating 12 Métis colonies — now known as the Alberta Métis Settlements, the only legislated Métis land base in Canada. Saskatchewan developed various Métis rehabilitation schemes such as Métis farms and colonies and special Métis schools, although these were shut down in the mid-1950s.

The dissolution of these road allowance communities began during the Depression. Through the Prairie Farm Rehabilitation Act in 1935, community or “co-op” pastures were created in rural areas, forcing many Métis out of their shanty communities. In places like “Little Chicago,” near Lestock, Sask., or Ste. Madeleine, Man., road allowance Métis families were forcibly removed. In Ste. Madeleine, all the homes were burned down and the families were dispersed to make way for a community pasture.

Despite being poor and facing racism on a daily basis, many Métis Elders remember the good parts of life on the road allowance positively. People danced to lively fiddle music at house parties. They visited while picking berries and digging Seneca root. They told wonderful stories, and they enthusiastically celebrated “li Zhoor di Laan” (New Year’s). Michif was spoken among community members, and the Elders provided a traditional education to the children. The Métis were independent and provided for their families the best they could. Community members helped one another, and families were close-knit. Even though life was difficult on the road allowance, many Métis Elders look back fondly to a time when life was simpler and people looked out for one another. Even though they were poor, they were rich in so many other ways.

Order now

from Amazon.ca or Chapters.Indigo.ca or contact your favourite bookseller or educational wholesaler