Traditional Ways

James Jerome was born on July 31, 1949, in the northern hamlet of Aklavik, N.W.T. He grew up, as generations of Gwich’in children had, in a camp on the land known as Big Rock by the Mackenzie River. His father, Joe Bernard Jerome, was a special constable with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, a trapper and chief of the Gwichya Gwich’in of Arctic Red River (Tsiigehtchic). His mother was Celina Jerome, née Coyen. The youngest of four brothers and two half-sisters, Jerome was able to spend years with his family, hunting and fishing, before having to attend Grollier Hall residential school in Inuvik, N.W.T.

At the age of 12, Jerome received a gift that would change his life — his mother gave him his first camera.

Both of Jerome’s parents died before he completed high school. After graduation, he trained as a welder and travelled around Canada before returning to his ancestral home in the Mackenzie Delta. There, his artistic inclinations were rekindled. As he spent time on the delta, his attachment to Gwich’in culture and traditions strengthened, as did his inspiration to record traditional ways that were gradually disappearing under the pressure of southern culture and technology.

Beginning in 1977, Jerome worked for the now defunct Native Press newspaper as a staff photographer for eight months before becoming a freelance photographer. His art took him into remote areas and into the skies for aerial assignments, though he also did studio work. While at Native Press he met professional photographer Tessa Macintosh, who’d recently arrived in Yellowknife to help train First Nations photographers. Macintosh recalled their meeting: “He’d applied for the job to study photography and learn on the job. It was for reporters that weren’t really trained in photography but enjoyed it and did it. We started working together, and sometimes we did the same job together. He had projects he found interesting and he had connections, so he’d go off and do them; stuff that was out there on the land and in the bush with First Nations friends.”

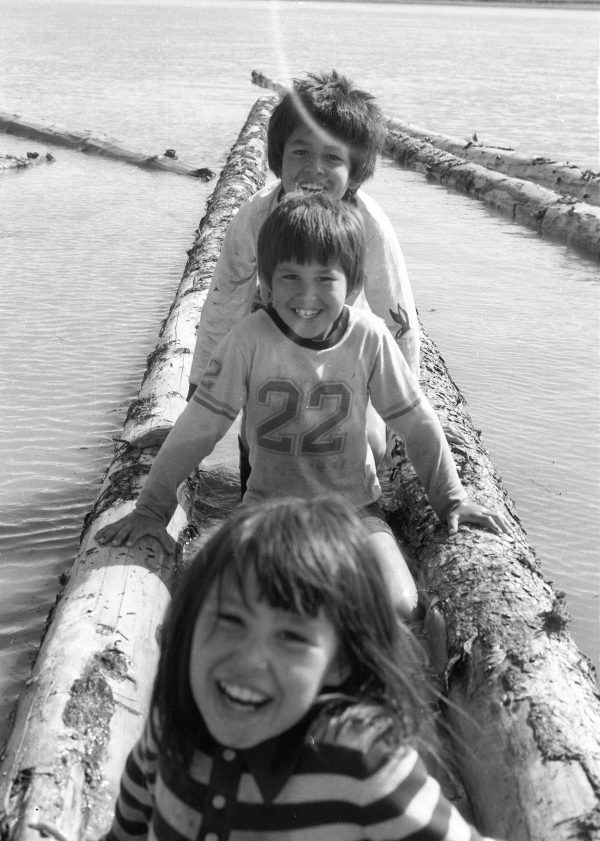

Over the next two years, Jerome took thousands of photographs around the Northwest Territories, including in Yellowknife and the South Slave region. Many of his photographs were taken in the Beaufort Delta region, documenting traditional Gwich’in life in the summer and winter camps and trapping and fishing activities along the river. He also travelled throughout the North, documenting large social events such as the Arctic Winter Games and the Northern Games in Inuvik. He produced an impressive portfolio of portraits, self-portraits, and photos of contemporary life in the towns. Jerome developed his photos in the darkrooms of a research centre in Inuvik (now known as the Aurora Research Institute), as well as the Native Press offices in Yellowknife.

Macintosh points out that Jerome was doing this work before the days where signed permission forms were required to take someone’s photograph. For that reason, there was very much an element of trust involved. “He certainly had a passion and an eye and he had a rapport with the people of the North,” she says. “I went back and reviewed the contact sheets of that time in the bush, and you can see he worked in sync with people. There was a rhythm involved, and he never bothered people. It was just understood in the old bush way. Trust is there because you live together. James would have been in the tent next door, eating together and hunting. Knowing James, he would have put down his camera and gone hunting as well. He was a real bushman.”

The career of this groundbreaking Indigenous artist was tragically cut short by a house fire in Inuvik on Nov. 17, 1979. Incredibly, thousands of his negatives were salvaged by his partner, Elisabeth Jansen Hadlari. Jerome’s portfolio, a collection totalling more than 9,000 negatives, was deposited at the Northwest Territories Archives in 1982, in trust for his son Thomas Hadlari. In 1995, Thomas donated the negatives to the archives for the benefit of future generations. These photographs provide an invaluable picture of Gwich’in and Dene life captured during the short period Jerome had to devote to his passion. At the time of his death, it is believed he was focused on finishing a book about Dene Elders of the Mackenzie Valley, titled Portraits and History of the Dene Elders. It is assumed that this work was lost in the fire that claimed his life.

Territorial Archivist Erin Suliak of the NWT Archives says many of the negatives were seriously damaged, though the archives were able to do vital conservation work in concert with the Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre to stabilize and preserve the collection. In 2008 and 2009, the archives received federal funding and were able to partner with the Gwich’in Social and Cultural Institute on an identification project (the GSCI’s mandate is to “document, preserve and promote Gwich’in culture, language, traditional knowledge and values”). “The success of the project was due entirely to this partnership,” says Suliak. “We were able to do identification workshops up in the Mackenzie Delta in the communities of Tsiigehtchic and Fort McPherson. It was just incredible. We got information about people, places and activities from Gwich’in Elders. We also worked with the GSCI to get the traditional Gwich’in names for all of the places. To me, this was such an important part of this project.”

Through this work, more than 3,500 of James Jerome’s photographs were catalogued with detailed descriptions and digitized by the NWT Archives, ensuring Jerome’s legacy will last for generations.

Order now

from Amazon.ca or Chapters.Indigo.ca or contact your favourite bookseller or educational wholesaler