Treaties

My father, Willie Joe, believed in the valour of Yukon First Nations and our pursuit of self-government. He sought to empower our people to create a better tomorrow for the generations to come. On Aug. 17, 1977, my father, president of the Yukon Native Brotherhood, sat down alongside his colleagues and across from Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau. They deliberated over a proposal to build a gas pipeline that would follow the Alaska Highway corridor. My leaders were in the middle of land claim negotiations for the area in question at the time and asked for more time to complete those agreements.

My father stated that they needed a further seven years to ensure that people in the community in their day-to-day social conditions could benefit from development rather than become victims of it. He added that while Yukon First Nations had been bureaucratically organized for the past eight years, instead of addressing social welfare, their energy had been largely spent locking horns with the federal government. The prime minister’s initial response was, “We all wish for more time.” He said that last-minute decisions “happen to us on every problem, foreign affairs, NATO, budget…but I think we have to make up our minds.”

To the prime minister, my father asking for a further seven years was the equivalent of saying no. Prime Minister Trudeau declared that you are either interested in development, running toilets and hydro dams or you are not. For my leaders, this extra time to ensure things were done right would benefit First Nations for years and generations to come, not just for the present. They weren’t saying “never;” they were simply saying “not right now.”

In 1973, our leaders sent a document to Prime Minister Trudeau entitled “Together Today for Our Children Tomorrow,” outlining our grievances and our approach to negotiations. Today, it could be understood as a pathway to reconciliation. The document stated: “The objective of the Yukon Indian people is to obtain a settlement in place of a treaty that will help us and our children learn to live in a changing world. We want to take part in development of the Yukon and Canada, not stop it. But we can only participate as Indians. We will not sell our heritage for a quick buck or a temporary job.” At the heart of this dispute was a foundational difference in the Indigenous approach to development: our vision is generations-long.

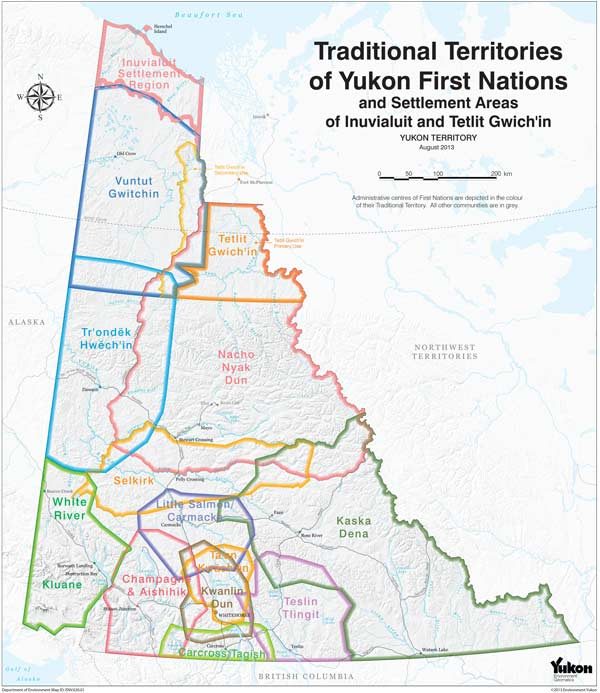

It was only after our leaders presented the federal government with that document that they started negotiating land claims across the Yukon. Unlike much of the rest of the country, there had never been any treaties or agreements signed there, despite outstanding claims dating back to the times of the Klondike gold rush. Spurred on by proposals to build the Mackenzie Valley Pipeline in the neighbouring Northwest Territories, the government created a federal royal commission, led by Judge Thomas Berger, to launch the Mackenzie Valley Pipeline Inquiry in 1974. The inquiry looked at the potential impacts of the pipeline on the environment, the economy and the people who lived in the area. Ultimately, they recommended a moratorium on all pipeline development in the area for 10 years, partly to allow for land claims to be settled.

Intergenerational leadership driven by devotion to our children is one of the key successes of Indigenous Peoples. It is a force that has and is changing how decisions are made.

The pipeline never came to fruition. However, after another 16 years of negotiation, by 1990 we had finalized both the Umbrella Final Agreement for the entire territory and a specific self-government agreement for my community, and I feel the Yukon is better for it. My leaders would not devalue people over economics, and as a result they were part of advancing the decision-making institution. Prior to the Mackenzie Valley Pipeline Inquiry, development decisions were based largely on economic values. Afterwards, it became the norm to evaluate environmental and socio-economic impacts through public consultation.

Would we have experienced the same level of success if the pipeline had been pushed through the next year? My instinct suggests not, and I’m thankful to our past leaders for their resolve to uphold the value of our people. My father and his colleagues stepped forward only considering my generation and our children. I am grateful for the opportunity, education and determination that our agreements have provided. Now, as I help further evolve decision-making, I strive to uphold the lessons of my past leaders and share my commitment to continuing our nation’s journey with my children.

This phenomenon of intergenerational leadership driven by devotion to our children is one of the key successes of Indigenous Peoples. It is a force that has and is changing how decisions are made. The achievement of our final agreements ensures we no longer have to jump at every opportunity. Instead, we are normalizing our approach, which is to take the time to do things right. While there’s still work to do to convince our colleagues in development of the value of prioritizing generations over year-to-year benefit, we are moving to a framework where our partners are actively seeking our Indigenous direction and wisdom. It is important to recognize that our leaders negotiated the agreements for all of Canada’s land and people. For this foresight, I am thankful. Today, I have more faith in the future of development as it’s evolving through new models of decision-making that are rooted in Indigenous values and visions of prosperity for the generations to come.

Order now

from Amazon.ca or Chapters.Indigo.ca or contact your favourite bookseller or educational wholesaler