Aftermath of 1885

The 1885 Northwest Resistance had a deleterious impact upon the Prairie Métis. Without question, the Battle of Batoche (the concluding battle of the 1885 Northwest Resistance) was Western Canada’s Plains of Abraham. It ensured that an Anglo-Protestant-led settler society would impose its dominance on the Canadian Prairies for several generations. Whether they participated or not, the outcome for First Nations and Métis peoples in Western Canada would be bleak. First Nations were forced to stay on reserves, and would only be allowed to leave via the infamous pass system. Their children were sent to residential and day schools to be assimilated.

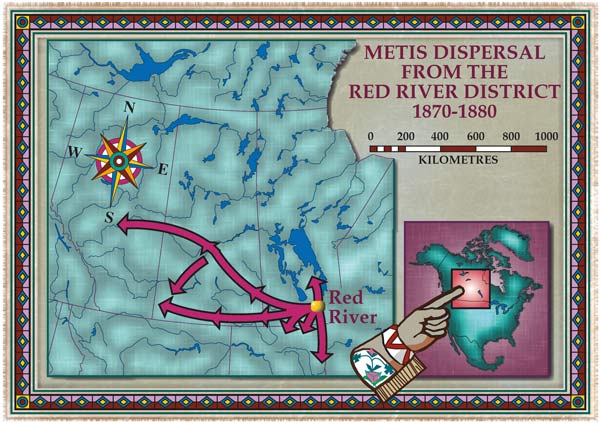

After the 1885 Northwest Resistance, many Métis were dispersed from their traditional lands to locations in the United States such as Fort Belknap or Lewiston in north central Montana and Turtle Mountain in North Dakota. Others would become the wandering nucleus of the Rocky Boy or Little Shell bands in Montana. Many already had kin in these locales and were going to their ancestral bison-hunting grounds. Others went north to parkland areas in what are now Saskatchewan and Alberta, or to the southern fringes of the Assiniboia district of the North-West Territories, later southern Saskatchewan and southeast Alberta. Other families stayed close to their original communities, near old hivernant (wintering) communities, fur trade posts and First Nations reserves.

All Métis, whether they participated in the 1885 Northwest Resistance or not, would face some very difficult choices about their place in this new society. Although only a few hundred Métis took up arms, the region’s Métis were stigmatized as “rebels.” This stigma of being labelled “rebels” or “traitors,” as well as facing unending racism for being Indigenous, forced many Métis, over several generations, to hide or deny their identity. As a result, many hid their Métis heritage and called themselves “French,” “French-Canadian” or “Scottish” to escape racism and for their own cultural safety.

Following the 1885 Northwest Resistance, the vast influx of non-Aboriginal settlers and the failure of the scrip system greatly disrupted the Métis’ traditional lifestyles. Most Métis would lose out in the Prairie West’s new social and economic landscape as newcomers flooded into the region. Throughout the 19th century, the Métis practised a mixed economy that included harvesting seasonal flora and fauna resources, supplemented with farming and wage labour. After 1885, however, most Métis would become socially, economically and politically marginalized. In most instances, the Métis didn’t have title to the land, and thus paid no taxes, which precluded their children from obtaining an education. With this marginal existence emerged a myriad of social problems, including poor health and self-esteem, and poverty.

The crux of Métis marginalization centred on the issue of land tenure. The fraudulent Métis scrip system, in which the vast majority of recipients never kept or received their scrip land, created a large number of landless, rootless Métis people. Many Métis rented the land or worked as labourers in towns and cities. Other Métis managed to keep their scrip land and owned it for a while, but lost their homesteads because they could not afford to pay their property taxes, particularly during the Depression of the 1930s. This was the case for the Métis at Cochin, Sask., and Ste. Madeleine, Man.

Because of their dispossession through the fraudulent scrip system, many, perhaps most, Métis never owned title to their lands. Many of them squatted along the approaches to rural roads or road allowances. Hence, the Métis were known as the “road allowance people.” Some of the main road allowance communities were settled by Métis returning to Canada from the United States. One example is Round Prairie, Sask. (formerly Prairie-Ronde), which was settled primarily by Métis who returned to Canada from the U.S. from 1903 to 1939. During the Depression, many of the residents of this Métis community moved to nearby Saskatoon. Other Métis from North Dakota settled in the Crescent Lake road allowance community near Yorkton, Sask.

Order now

from Amazon.ca or Chapters.Indigo.ca or contact your favourite bookseller or educational wholesaler