Communities

The Métis are one of Canada’s fastest growing demographic groups. According to Canada’s 2011 census, 451,795 people identified as being Métis. The Métis National Council represents the almost 400,000 self-identified Métis living in Ontario and the four western provinces. According to 2011 census data, about 85 per cent of self-identified Métis in Canada live in these five provinces. Alberta had the largest Métis population with 96,865 residents, followed by Ontario with 86,015, then Manitoba with 78,830, British Columbia with 69,475, and Saskatchewan with 52,450. It should be stated that there is not yet a proper Métis National Council enumeration of the citizens of the Métis Nation. Once that enumeration takes place, the numbers of Métis citizens will likely differ from the census numbers. The Métis primarily live in urban areas, including large cities, metropolitan areas, and smaller urban centres. Winnipeg has the largest Métis population in Canada, with 46,325 residents. Edmonton has the second highest Métis population, with 31,780 residents. Other centres with large Métis populations include: Vancouver (18,485), Calgary (17,040), Saskatoon (11,520), Toronto (9,980), Regina (8,225), Prince Albert, Sask. (7,900) and Ottawa-Gatineau (6,860). According to the 2006 census, Métis living in urban areas are twice as likely to live in smaller centres (populations of less than 100,000) than non-Indigenous people in urban areas. Approximately 41 per cent of urban Métis live in these smaller urban centres. Many Métis also live in rural areas, largely in or near Canada’s boreal forest in communities such as the Alberta Métis Settlements (approximately 5,000 residents) and in numerous other communities such as Île-à-la-Crosse, Sask., Duck Bay, Man., and Fort McKay, Alta.

The Métis are also a relatively young population. In 2011, the median age of the Métis in Canada was 31, while the non-Indigenous median age was 41. The Métis had the oldest median age of the three Indigenous groups in 2011: Inuit had a median age of 23, and First Nations people with registered Indian status had a median age of 26. The youngest Métis populations lived in Alberta and Saskatchewan, where the median age was 28. There were also 104,415 Métis children aged 14 and under living in Canada. The majority of them, 60,605 (58 per cent), lived with both parents, 31,095 (nearly 30 per cent) lived in a one-parent family, and 8,935 (8.6 per cent) lived in a stepfamily. A small percentage of Métis children (1,400 or 1.4 per cent) lived with their grandparent(s) and nearly 1,800 (1.7 per cent) were foster children.

Chris Andersen, author and professor in the faculty of native studies at the University of Alberta, has noted that in recent years Canadian censuses have seen an increase in the number of people self-declaring as Métis. Although the exact cause of this increase is unknown, it can’t be explained by natural demographic factors alone. Andersen offers several explanations for this increase, including the possibility of a new-found feeling of safety to identify as Métis after a history of persecution, as well as the perceived government benefits can be obtained. Another explanation is the phrasing in the census itself, and the categorization of Métis as a racial category (mixed Indigenous, Euro-Settler) rather than a distinct Indigenous nation based mainly in Western Canada. As a result, many people are claiming to be Métis based on various amounts of mixed Indigenous and Settler ancestry, even if they have no connection with the Métis Nation.

Historic Métis Communities

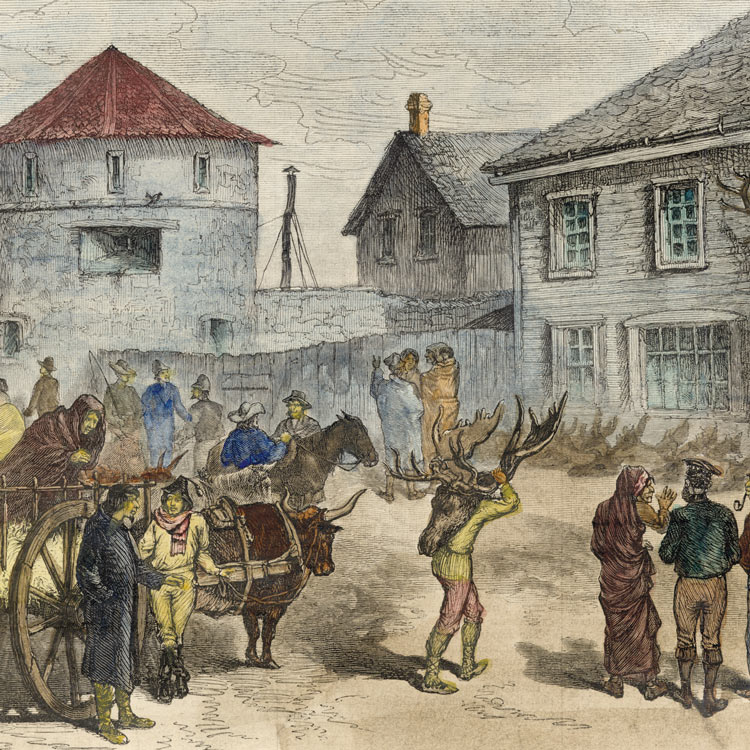

The Métis Homeland is extensive and includes dozens of historic communities in Western Canada, northwest Ontario, Northwest Territories, Montana and North Dakota. Many of these communities are well-known, such as Winnipeg, Batoche and Prince Albert in Saskatchewan and Edmonton, but others are not, such as Chicago Line or “Little Chicago,” near Lestock, Sask. Some communities were temporary, such as hivernant or wintering sites—many of which have been found in Manitoba, Alberta and Saskatchewan.

The Métis have often been characterized by their high mobility, and the earliest Métis settlements were occupied seasonally.

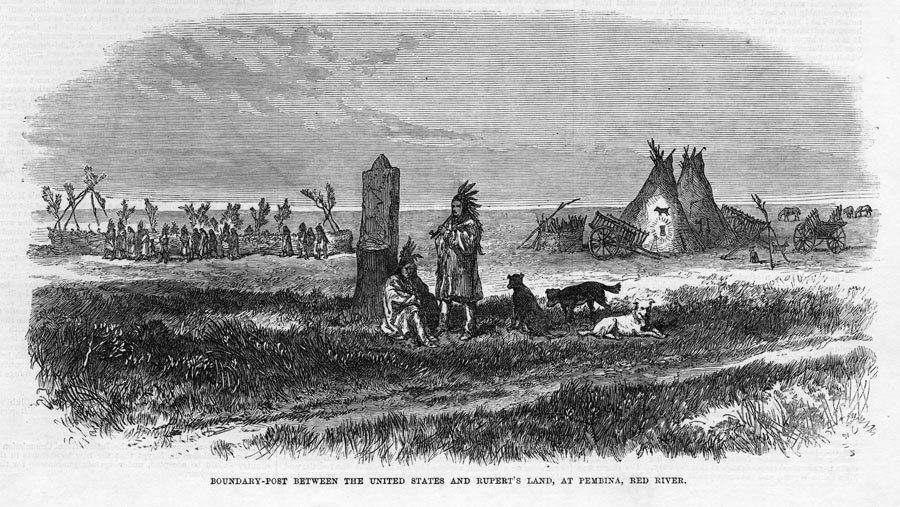

The Métis have often been characterized by their high mobility, and the earliest Métis settlements were occupied seasonally. These settlements were also closely associated with their connections to the fur trade, their control of the transportation system in the historic Northwest, and their bison-hunting activities on the plains. Many communities were established around the earliest fur trade forts, at important transportation stopping points, and at the wintering sites of the Métis plains hunters. Other settlements were near important fishing locations. The numerous Métis road allowance communities denote the dispossession and dislocation of the Métis after the 1869-70 and 1885 resistances. In the post-1885 period, an influx of European settlers drove the Métis further and further west. The Michif, Cree, Ojibway, Dene and French names the Métis used to identify their settlements soon disappeared, as settlers renamed the locations.

The government of Canada dealt with the Métis on an individual basis rather than through group negotiations under the Manitoba Act (1870) and Northwest Scrip commissions, which issued land to the Métis under the Dominion Lands Act. This well-documented assimilation policy resulted in the Métis being dispersed widely in their homeland. However, large numbers of Métis can still be identified living in the vicinity of their historic settlements.

In Canada, hunting and harvesting rights are high on the Métis agenda. This has been particularly true since the Supreme Court’s Powley decision (September 2003) established a legal test to demonstrate hunting and harvesting constitutional rights for Métis throughout Canada. It has therefore become even more important to establish how the Métis hunted and harvested across the historic Northwest before there was a U.S.-Canada border and before provincial and territorial boundaries were drawn. To this end, the Métis National Council and its Governing Members have been documenting the history of Métis settlement and resource use across the Métis Nation Homeland.

As Métis studies has developed as an academic discipline, numerous Métis groups, aided by historians and anthropologists, have conducted interviews with Elders in order to document the Métis Nation Homeland and the historical viewpoint of Métis citizens.

Road Allowance People

After the 1885 Northwest Resistance, many displaced, landless Métis squatted on Crown land set aside for the creation of roads in parts of the Prairie provinces of Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba. This Crown land became known as “li shmaen dii liings” in Michif. Métis “squatting communities” could be found along road allowances or railways, marginal patches of land such as hillsides, edges of First Nations reserves, along city or town fringes, near garbage dumps, in the northern bush or in unsettled parkland areas, and along provincial and federal forests. In these locations, the Métis risked being further displaced by government authorities.

Order now

from Amazon.ca or Chapters.Indigo.ca or contact your favourite bookseller or educational wholesaler