Connection to the Land

Growing up as a “rez kid” in my home community of Chisasibi (Cree for “Big River”), I always loved hearing the stories my dad, Stephen Pashagumskum, would tell of his great adventures growing up on the land. My dad was born on May 12, 1947, in a teepee, deep in the forests of Quebec on the shores of a lake that no longer exists. It was lost to flooding in the late 1970s to create the Caniapiscau Reservoir as part of Hydro-Québec’s James Bay Project.

In my dad’s times, the traditional gathering place in the summer for our people was Fort George, an island located at the mouth of the Chisasibi River where it opens into James Bay. Every spring, Cree families would make their way back to this place for the summer. Each family would arrive in their own canoe and set up their teepee on their favourite summer spot. Spots were arranged by families, and groups of teepees would be set up beside each other to form a circle.

This is how all the family groups would set up their camps, with a communal area in the middle where the kids would play. Most families had teepees, but the ones that could afford it lived in prospector tents. These were usually the families that had had a good trapping season and did well trading furs.

The island was a place of gathering where our people could reconnect with family and friends. Fort George was also a place to celebrate events together, like weddings and walking out ceremonies for young children touching the Earth for the first time.

Before the relocation, people lived a more traditional way of life.

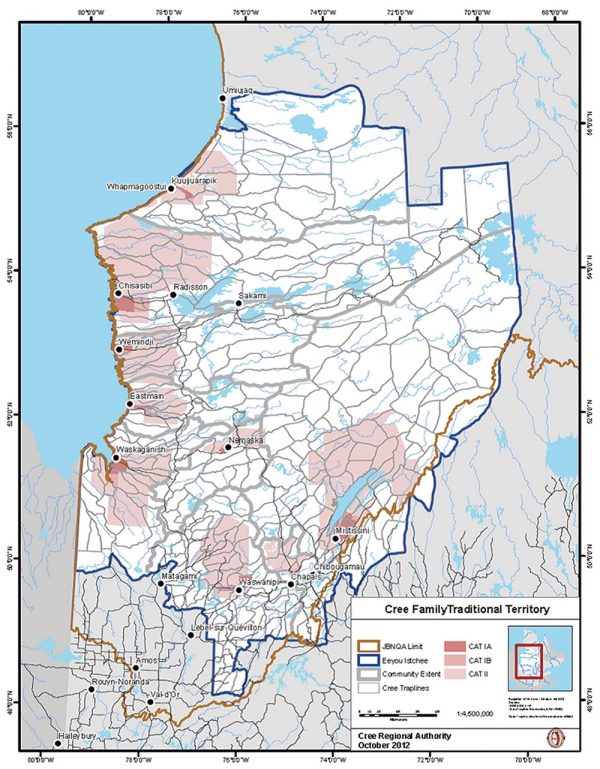

Once summer was over, families would pack up camp and head back out on the land to their respective hunting grounds to set up their fall and winter camps. Our family’s hunting grounds were upriver in the area known as Caniapiscau. The traditional winter dwelling was the Mihtukan or “wooden lodge.” The Mihtukan is similar to a wigwam, like a teepee made of wood instead of canvas and insulated with sod. These shelters could be constructed to fit any size family and could lodge up to three families if necessary. Unlike the permanent housing of today, Cree traditional homes were adaptable and easily raised and taken down.

In 1980, the government pushed for us to move into Chisasibi and abandon the island, concerned that it would be lost to erosion. (In the end, it wasn’t, and some people still go back there.) It was a sudden change, to go from living off the land to living in a modern town within a year, and it served to distance people from the land in many ways.

Today, like many other First Nations communities in Canada, the Eastern James Bay Cree live in modern houses, constructed on behalf of the local government and partially funded by the on-reserve non-profit housing program, part of the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation. For the most part, these houses are rental units mortgaged by the Band. However, due to low employment and high costs of living, rent collection on-reserve is difficult. This lack of revenue for the local government means less money for maintenance. When this is coupled with the overcrowded living conditions due to a shortage of housing, the buildings become dilapidated quickly. Overcrowding can also lead to health issues, like mould, and problems for the children at school. They often have trouble getting enough sleep in an overcrowded home, and this affects their ability to learn. This current housing situation is a far path from the traditional lifestyle of the Cree.

My dad still looks fondly back on the carefree days of his youth and often reflects on his life. Back then, he recalls, every family had their own home. Once a person was married they would live in their own dwelling — mostly the Mihtukan, but also teepees or tents while on the move. But that all changed once the people moved off the land onto reserves. This had the effect of splitting the families and, in turn, splitting the Cree Nation. From then on, everything was done according to Waamishtikushiiu — “the white man.” After a while, our society became more materialistic. There was a shift from survival to gaining material things.

Before the relocation, people lived a more traditional way of life. Afterwards, people enjoyed modern amenities, like plumbing and electricity, and a hospital in town. But it also made people more dependent on these things. Before, people would spend up to six months out on the land, from the fall to the spring, hunting and trapping. Now, most people take just two weeks off for the “goose break” every year. While there are other programs to teach children about our culture and language, it often seems like the solutions are just temporary bandages on a deeper problem.

My dad always said they survived so well before because they had my grandfather, David Pashagumskum. He used to tell them, “Take care of this land, and this land will take care of you.” It really is important that we listen to the teachings of our Elders, or we risk losing everything we have and are.

Order now

from Amazon.ca or Chapters.Indigo.ca or contact your favourite bookseller or educational wholesaler