Identity

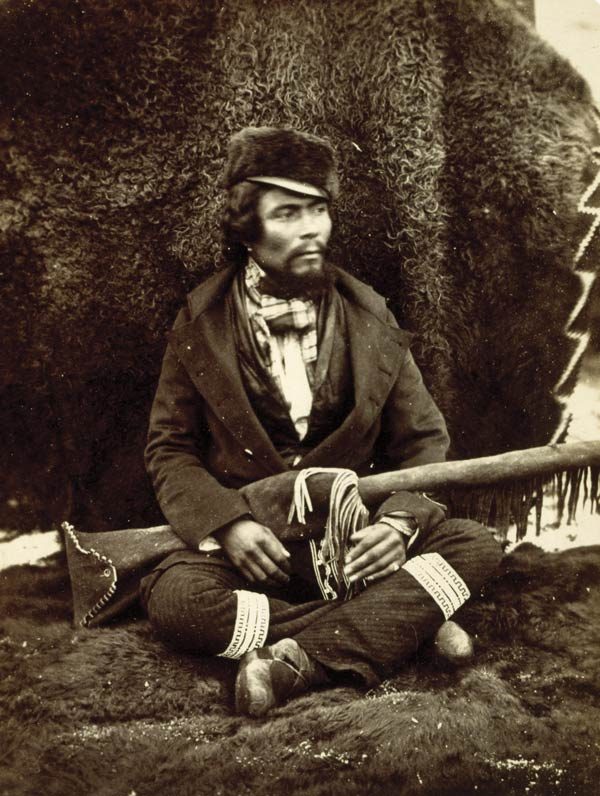

Canada has a founding people who once traversed North America’s interior in Red River carts, hunted bison with military precision, danced and jigged to spirited fiddle rhythms, wore brightly adorned embroidered clothing, spoke one of humanity’s unique languages, prayed to Li Bon Jeu/Kitchi Manitou and to their patron saint, St. Joseph, and even had their own werewolf. These people were the Métis.

Within non-Indigenous society, there are two competing ideas of what being Métis means. The first, when spelled with a lowercase “m” (métis), means individuals or people having mixed-race parents and ancestries, e.g., North American Indigenous and European/Euro-Canadian/Euro-American. It is a racial categorization. This is the oldest meaning of Métis and is based on the French verb métisser, to mix races or ethnicities. The related noun for the act of race-mixing is métissage. The second meaning of being Métis, and the one that is embraced by the Métis Nation, relates to a self-defining people with a distinct history in a specific region (Western Canada’s prairies) with some spillover into British Columbia, Ontario, North Dakota, Montana and Northwest Territories. In this case, the term Métis is spelled with an uppercase “M” and often, but does not always, contain an accent aigu (é).

Being a big “M” Métis relies on having a political-cultural definition of Métis identity because — while it recognizes that being Métis is not just about having ancestry that is Indigenous (usually Cree, Saulteaux and Dene) and European/Euro-Canadian (usually French-Canadian, Scots and Orcadian) — it relates to a community of people who self-identify as being Métis and recognizes that their ancestors made a political decision to identify as Métis based on shared histories and culture.

To proponents of this type of Métis identity, being Métis means more than just having mixed Indigenous-European ancestry. If that were the case, virtually all First Nations in Canada and French-Canadians and Acadians would be Métis as a result of genetic and cultural mixing in the earlier colonial period. However, in each of these cases, First Nations, French-Canadians and Acadians recognize that their various ancestors contributed to the “stew” of their various ethnicities, and their ancestors made a conscious decision to self-identify as distinct nations of people and not as mixed-race nations. Being Métis in this sense is about making a conscious decision to identify with a community of other like-minded people. The historic Métis had distinct cultures and lifeways, were recognized as being their own people and were given distinct names by Indigenous nations and by the European fur traders, such as Otipemisiwak, Apeetogosan, gens libres and Bois-brûlés.

Big “M” Métis identity focuses on the following criteria: the Métis developed during the fur trade in what is now Western Canada and part of northwest Ontario; they have roots in the Red River Settlement or in fur trade communities in the northern reaches of the Prairie provinces; they received land grants or scrip to address their Aboriginal title (through the Manitoba Act and the Dominion Lands Act); and they were recognized as a distinct Indigenous nation by other Indigenous nations, by Europeans and Euro-Canadians, and by colonial (U.K.) and settler governments (Canada). This community of people had a political will to create their identity and formed the historic Métis Nation. In time, this identity developed into the modern Métis Nation, which includes all their descendants who self-identify as being Métis and are recognized as such by other community members. They are tied to their ancestors by living in traditional Métis lands, self-identifying as Métis, practising their culture and, when possible, speaking Michif and other languages.

Métis “peoplehood” or big “M” Métis identity is complicated by the fact that many Métis moved to other parts of Canada and the United States as part of the Métis diaspora after 1885 and to find better employment opportunities later on. Much of the core membership of the Métis Nation British Columbia and the Métis Nation of Ontario are descendants of Prairie Métis who moved out to these places for better economic opportunities.

Modern Métis Political Identity

Métis identity has evolved in more recent times. In the 1960s, the old names used by the various historical Métis communities to describe themselves (such as Half-breeds or “Michifs”) gave way to “Métis” and the creation of a pan-Métis identity. Around the same time, there was a recognition that both non-status Indians and Métis had a great deal in common as unrecognized Indigenous peoples. As a result, non-status Indians and Métis shared common political lobbying organizations through the 1970s and early 1980s. The Native Council of Canada was founded in 1971 by Métis political organizations from the three Prairie provinces as a national lobbying organization. It soon expanded to include non-status and “other” Métis groups from across the country. In time, the Métis political bodies on the Prairies would have many non-status members, and this unity of non-rights-holding Indigenous peoples was reflected in the name Association of Métis and Non-Status Indians of Saskatchewan. By the early 1980s, the Métis from the three Prairie provinces left the Native Council of Canada (whose national leadership was almost exclusively non-status and Status Indians) to create the Métis National Council in 1983. The new MNC was dedicated exclusively to advocacy for the rights of the Métis Nation. While the Manitoba Metis Federation and the Métis Association of Alberta became Métis only, the Métis Society of Saskatchewan was not established unil 1988 when the provincial membership voted to establish a Métis-only political body. Many non-status Indians would later acquire their status via Bill C-31 and would leave Métis political organizations.

The MNC represents Métis in the four western provinces and Ontario. It does not include Métis communities in the Northwest Territories that are part of the Métis Nation, but have their own rights process with the federal government that they do not wish to jeopardize. The MNC represents the big “M” Métis and adopted the following definition of being Métis in 2002: “Métis means a person who self-identifies as Métis, is distinct from other Aboriginal peoples, is of historic Métis Nation Ancestry and who is accepted by the Métis Nation.”

Order now

from Amazon.ca or Chapters.Indigo.ca or contact your favourite bookseller or educational wholesaler