Lifeways

Traditionally, Métis families and communities traversed the landscape following the reproductive and ripening flora and fauna cycles, which meant adapting their lives to the changing seasons. The Métis had to be flexible in order to work well together in times of plenty and to work independently when resources were scarce. The seasonal cycle was also affected by the availability of employment opportunities and the cultivation of garden crops or cereal agriculture. A family may have spent the late spring and early summer in a home community where they planted a garden and a plot of wheat, or they may have spent the late summer involved in bison hunting, the fall in berry collecting, the winter in trapping or as part of a winter bison-hunting camp, and the early spring at a fishery.

Today, Métis who live traditional lifestyles still maintain this focus on seasonal cycles. Natural signs indicate to the Métis when it is time to begin a particular activity and when to finish others. For instance, for the Métis of the Paddle Prairie region of northern Alberta, the seasonal cycle begins in Niskipisim or Goose Moon (March), when geese begin their migratory flight to northern nesting grounds, announcing the arrival of spring. All exposed grass, stubble fields and dead leaves are burned at this time to renew the forest and meadows.

Weather conditions also play a role in the harvesting of resources. For instance, during periods of frequent drought, a situation quite common on the Prairies, the harvesting cycle for such animals as bison, moose, wapiti (elk), and white-tailed and mule deer is adversely affected. Berries such as saskatoons and chokecherries also grow sporadically in periods of prolonged drought. In such situations, Métis who follow the seasonal cycles have to substitute those scarce goods with other resources, often further afield. This may mean trapping and hunting smaller fauna such as muskrats and prairie chickens (sharp-tailed grouse) or harvesting fish such as pike, pickerel or sturgeon. As a result, there is not one seasonal cycle, but many.

Taking part in a seasonal cycle is a spiritual exercise because the participant is part of a holistic system with all things in creation. Resources are gifts from the Creator for all humans to share. Therefore, when harvesting resources, Métis follow traditional ways and always leave a gift for the Creator, usually tobacco or tea. If a gift is not left when a resource is harvested, the community runs the risk of losing that resource.

Traditional Métis Medicines

Like most Indigenous peoples, the Métis have their own traditional medicines. Métis medicine is holistic and focuses on the individual’s mental, emotional, physical and spiritual capacities. Traditionally, Métis women were healers and midwives who provided a large assortment of medicines (known as “la michinn” in the Michif language) to heal family and community members. Today, both Métis women and men are healers. Rose Richardson of Green Lake, Sask., is a widely respected Métis healer and medicine woman. She is one of many healers and medicine people within the Métis Nation.

Métis medicines almost always include traditional Indigenous plants and remedies, although a few medicines have been handed down from the Métis’ Euro-Settler ancestors. Most medicines are gathered from the local natural environment, and many of the same medicines are used across the Métis Nation Homeland. In the February 2011 edition of Eagle Feather News, Métis author Maria Campbell wrote, “Our drug store was half a mile up the road in a meadow called Omisimaw Puskiwa (oldest sister prairie) where yarrow, plantain, wild roses, fireweed, asters, nettles, and pigweed could be found in great abundance. Some of it was just medicine and some of it like fireweed, nettles, and pigweed was medicine and food.”

Medicines are gathered locally and are dried and stored in the home, where they are either ground into a powder or made into tinctures, teas, poultices and salves. They are used as painkillers, anti-inflammatory agents and digestive aids, and to treat very specific ailments including arthritis, asthma, diabetes, gastrointestinal issues, tuberculosis, cancer, headaches, toothaches, colds, kidney stones, gallstones, venereal diseases, menstruation, cuts and rashes. When gathering the plants, certain protocols must be adhered to; a prayer of thanks to the Creator is required and tobacco or another “gift of thanks” must be offered. Moreover, medicine gatherers should harvest only what is needed, and no plants should be harmed while harvesting.

There are four sacred herbs and lead medicines that the Métis use—sweetgrass (fwayn seukrii, fwayn di bufflo), cedar (li sayd), sage (l’aarbr a saent) and tobacco (li tabaa). These herbs are used for cleansing, for sacred offerings and for prayer. Some other Métis medicinal plants are burdock (li grachaw), balsam (la gratelle), wild sarsaparilla (sasperal), blueberries (lii grenn bleu), broad-leaved plantain (plaanten), chokecherries (lii grenn), cow parsnip (berce), highbush cranberries (lii paabinaw), lowbush cranberries (moosomina), dandelion (pisanli), ginger root (sayn Jean, rasyn), hazelnut (pakan), hemlock (carrot à moreau), juniper (aean naarbr si koom aen nipinet avik lii gren vyalet), Labrador tea (lii tii’d mashkek), oak bark (ii kors di shenn), rosehip (lii bon tiiroozh), Seneca root (la rasinn), snakeroot (la rasinn di coulyv), spruce gum (gum di sapin), stinging nettle (mazhaan), rat root (Belle-Angélique, weecase), wild mint (li boum), wild onion (zayon faroosh), wintergreen (pipisissew) and yarrow ( li fleur blaan).

Medicines that can be harvested from animals include burbot (mariah, freshwater cod) liver oil, fish milk (bouyon or broth), goose grease and skunk oil (wil de shikaak). Medicines are also made from sucker heads, and muskrat. Many animals eat plant medicines and as a result, they can be considered medicines as well.

Seasonal Cycles

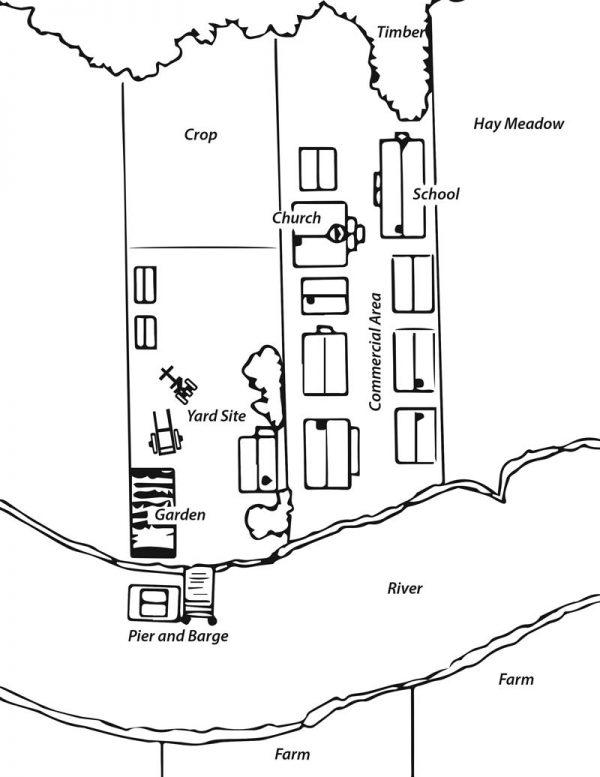

A typical seasonal cycle for Métis living in the Red River Settlement in the mid-19th century:

Spring

Hunting ducks, geese, swans, prairie chickens, pheasants, partridges, male moose, male deer, male wapiti (elk) and prairie grizzlies. Catching spawning fish such as pike, walleye and sturgeon with weirs, nets, spears or traps. Trapping or hunting mink, otters, beavers, muskrats, rabbits, coyotes and wolves. Collecting birchbark for canoes and household items. Tapping birch and maple trees, and seeding wheat and other grains.

Summer

Hunting bison in order to pay off debts to Hudson’s Bay Company incurred in winter and to restock food supplies. Hunting wolves, coyotes, bears, prairie chickens, rabbits, moose, deer, and wapiti. Trapping bears. Gathering Seneca root, blueberries, saskatoon berries, raspberries, currants, gooseberries and chokecherries. Fishing with nets. Seeding and harvesting barley. Shearing sheep.

Fall

Hunting bison to provision posts and secure winter food supply. Hunting moose, deer, wapiti, prairie chickens, and migratory ducks, geese and swans. Fishing for spawning fish, such as whitefish and salmon, with weirs, nets, spears or traps. Trapping or hunting bears, wolves, coyotes, mink, otters, beavers, muskrats and rabbits. Harvesting ripening wild rice, chokecherries, saskatoon berries and highbush cranberries. Harvesting wheat. Slaughtering livestock.

Winter

Trapping weasels, skunks, mink, otters, beavers, muskrats, bears, foxes and lynx. Hunting bears, wolves, coyotes, prairie chickens, rabbits, moose, deer and wapiti. Ice fishing with nets. Hunting bison in winter camps.

Order now

from Amazon.ca or Chapters.Indigo.ca or contact your favourite bookseller or educational wholesaler