Worldview

In the Michif language there are many different names and alternate spellings for God, including Li Bon Jeu, Kitche Manitou, Gitchi Manidoo and Not Kriiteur. Métis spirituality is reflected in the diversity of Métis people themselves; many Métis are Catholics, others are mainline Protestants, some are evangelical Protestants, some are Jehovah’s Witnesses, others are Mormon, many more adhere to the old “Indian religions,” and some blend Christianity with traditional Indigenous spirituality.

Historically, many Métis practised spiritual syncretism, mixing Catholicism with the Plains Indigenous religions. For instance, Gabriel Dumont was a practising Roman Catholic, but he was also a pipe carrier in the Plains Indigenous spiritual tradition, and on his land there were Dakota sweat lodge frames. Gabriel Dumont did not see a conflict with being both a Roman Catholic and a follower of Plains Indigenous spirituality. This mixed spiritual practice was very common among many traditional Métis.

Traditional Métis Catholicism focuses on the Creator. Prayers of thanks are given daily, and offerings are left when taking from the Creator’s bounty. Stories are told to children that blend aspects of Algonquian storytelling and spirituality with Catholicism (especially during Lent) to ensure that they follow their obligations to the Creator. Another important practice involves the veneration of the Virgin and the saints as well as prayers for their intercession. Pilgrimages to St. Laurent de Grandin, Sask., and Lac Ste. Anne (Manitou Sakahigan), Alta., and other locales are well-attended every year. Abstinence, self-sacrifice and purification rituals are particularly important, especially during Lent or when attending sweats. The concept of Good Works, especially helping the less fortunate, is strongly adhered to.

Respect for the dead is a cornerstone of traditional Métis spirituality. When loved ones die, wakes are usually held for four days. Ancestors are remembered and honoured through prayers and offerings. All Souls’ Day (Nov. 2) is an important liturgical event. Often when feasts are held, an extra table setting with food and cutlery is set for the ancestors, and after the meal concludes, the food is put into a fire to honour them. The northern lights, or “lii chiraan” in Michif, are believed to contain the souls of the dead who are dancing. Métis Elders say that you should never whistle at the northern lights, otherwise the dead will take you away. This belief is from the Métis’ Cree and Ojibway ancestral cultures.

Many Métis had their faith shaken by the abusive church-run residential school system. Despite these devastating events and ongoing colonization, many Métis remain spiritual people. At present, many Métis youth and urban Métis are embracing First Nations spirituality and attending sweats and other First Nations purification ceremonies.

Métis Elders

Métis Elders teach younger generations about Métis history, lifeways and culture. In Michif, Elders are called “lii vyeu” or the “old people.” They were also known in Michif as “Ahneegay-kaashigakick” or “the ones who know.”

In Métis communities, Elders are the main source of historical and cultural information. In the past, events were not recorded on paper, but were passed down by Elders through the Oral Tradition. Not all elderly people are considered Elders in Métis communities. To be an Elder, the person must be wise and caring, and should show a willingness to share information with others. Elders must also live a balanced life and not be judgmental of others. They must also be viewed by community members as an Elder. There are different kinds of Elders — some practise medicines, some are language keepers, some are midwives, and some tell stories and possess and share other aspects of traditional knowledge.

When working with Elders, you must follow strict protocols. When sharing information or stories related to Elders, you must first seek their permission, and you must acknowledge them when relating the information. You should always present Elders with a gift for sharing their wisdom with you. This could be a tobacco offering or a small gift (something that they can use or appreciate) or an honorarium. Also, at public gatherings, Elders are always acknowledged and served first at mealtime.

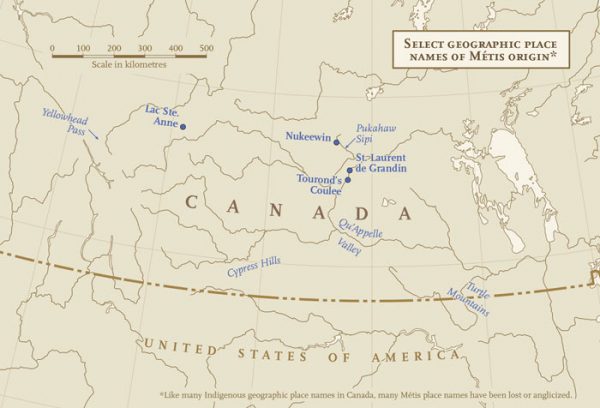

Métis Geographic Names

Like other Indigenous peoples, the Métis have their own geographic names for land and bodies of water. However, as a result of Euro-settlement and colonization, many Métis geographic names have been lost, replaced or anglicized. Often, these names are in a Métis heritage language such as Michif, Cree or French.

Perhaps the most noticeable land form in Western Canada that has a Métis place name is the Cypress Hills. Métis bison hunters called the hills — the highest elevation in Canada east of the Rockies — “montagne de cyprès” because of the many jack pines in the region. The Métis used to call pine trees “cyprès,” even though they are not proper cypress trees. The name for the hill formation was then anglicized to “Cypress Hills.”

Another famous landform in Western Canada is the Yellowhead Pass near Jasper, Alta. It is also the name of the well-known Yellowhead Trans-Canada Highway, among other things. The original name of the Yellowhead Pass was “Tête Jaune,” meaning “yellow head” in French. It was named after Pierre Bostonais, a famous Iroquois-Métis trapper with a mane of golden hair, who guided Hudson’s Bay Company through the pass in the early 1820s.

The Qu’Appelle Valley in Saskatchewan is known as Kâ-têpwêt (“who calls?”) in Cree. The Métis kept the name and adapted it to the name of the valley and to one of their road allowance communities, Katepwa, which extended across the length of the valley.

Another prominent geographic feature in southwest Manitoba and northeast North Dakota with Métis provenance is Turtle Mountain, or Turtle Mountain Plateau. In Michif/French, the Métis called this wooded uplands, “la montagne tortue.” A well-known Métis folksong in Michif has the same name.

Reclaiming or restoring traditional place names is important to many Métis. A major Métis name restoration occurred in 2007 when the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada agreed to change the name of the 1885 Battle of Fish Creek National Historic Site (a monumental location in the 1885 Northwest Resistance) to the Battle of Tourond’s Coulee/Fish Creek to recognize the Métis community name for this place, Tourond’s Coulee. This change required a great deal of lobbying by the local Métis community, the Gabriel Dumont Institute, Friends of Batoche and Parks Canada. Many in the Métis community are working to restore other Métis geographic names and to commemorate them.

Often, name changes to Métis places or geographic features are documented in the historical record or have been chronicled in the Oral Tradition. Métis author Maria Campbell wrote about the area around her Métis road allowance community, Nugeewin—the stopping place — in her acclaimed autobiography, Half-Breed. Nugeewin was where Indigenous people stopped on their way to cross Puktahaw Sipi, or Net-Throwing River, to get to their hunting and trapping grounds. In 1925, Nugeewin was replaced by Park Valley. In 1915, the federal government decided to turn the surrounding territory into a national park (later officially named Prince Albert National Park), displacing many local Métis and Cree. This displacement also resulted in local Indigenous names for lakes and rivers being changed. For instance, Puktahaw Sipi became Sturgeon River, and Notikew Sahkikun became Mariah Lake. The erasure of Métis place names and geographic features in this fashion occurred across the Métis Homeland.

Order now

from Amazon.ca or Chapters.Indigo.ca or contact your favourite bookseller or educational wholesaler