Origins

“We are the rightful owners of our tribal territory… We have always lived in our country. At no time have we ever deserted it, or left it to others… Our ancestors were in possession of our country centuries before the whites came. It is the same as yesterday when the latter came, and like the day before when the first fur trader came.” These statements were made by leaders of the St’át’imc, later known as “the Lillooet people,” who made a formal declaration to the federal government in 1911 over land rights to their tribal territory. This territory is located in what geographers refer to as the Plateau region of Canada — a high plateau nestled between British Columbia’s coastal mountains and the Rocky Mountains in the southern region of the province.

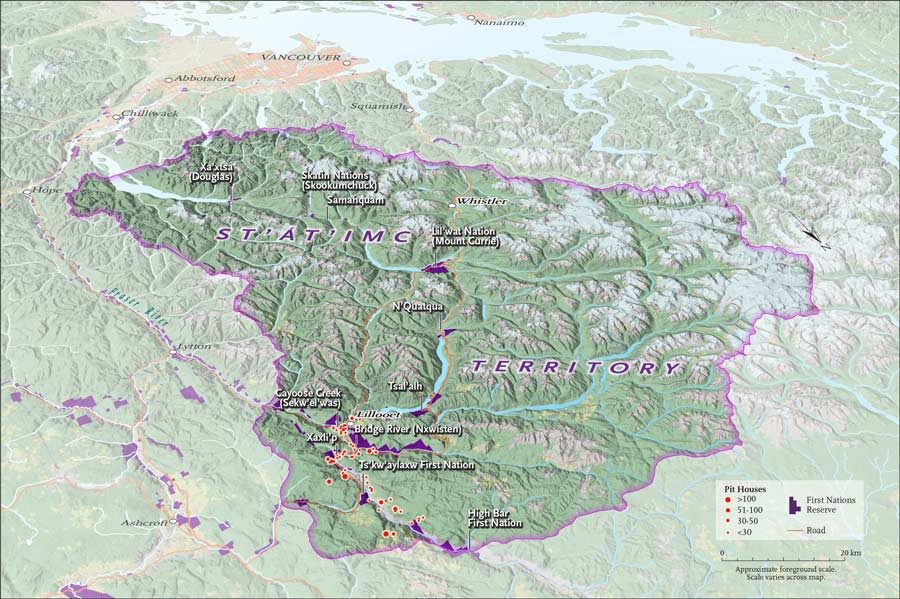

The St’át’imc self-identify as the original inhabitants of the territory that extends north to Churn Creek and to South French Bar Creek, northwest to the headwaters of Bridge River, north and east toward Hat Creek Valley, east to the Big Slide, south to the island on Harrison Lake, and west of the Fraser River to the headwaters of Lillooet River, Ryan River and Black Tusk Lake. In their Interior Salish language, one would say, “Ci wa lh kalth ti tmicwa (the land is ours). We are ucwalmicw (the people of the land).”

When I was a young child growing up in Toronto, Mom used to describe this place where she was born and raised, but I couldn’t really visualize it until I finally visited Lillooet myself as an adult with my wife one summer, long after Mom had passed on to the spirit world, and more than 100 years after the St’át’imc chief wrote the 1911 Declaration of the Lillooet Tribe. As I drove to my mom’s home, Xaxli’p reserve (formerly known as Fountain Band), I struggled to take it all in. Boreal forests, mountains, valleys, lakes and rivers contrasted against train tracks and greyish-brown hills with blackened tree stumps left sticking up after a recent forest fire. Vehicles behind me honked to get me to drive faster, but I couldn’t with all the distractions of sharp turns in the road, warning signs of falling rocks, trucks hauling massive loads of logs, and steep cliffs to sharp rocks and the Fraser River below. I can’t imagine what it must have been like to live and travel in the mountains before the highways were built, but it’s easier to understand now why Mom said going to the town of Lillooet with family members was a big deal when she was a child.

Ci wa lh kalth ti tmicwa

(the land is ours).

We are ucwalmicw

(the people of the land).

During my trip west, my cousins were excited to take us to their traditional fishing grounds on the Fraser River where, for generations each summer, salmon were caught and wind-dried in the scorching heat. Art Adolph, former chief of Xaxli’p and a relative, told us legends and stories, including traditional knowledge involving salmon, such as when the buttercup and rose bush blooms indicate certain salmon runs have arrived in the territory and when a distinctive clicking sound made by the grasshopper signals the proper time to wind-dry salmon. It was easy to understand that with the annual return of the salmon, along with the annual rehabilitation of fishing grounds, the St’át’imc are rejuvenated and empowered with their annual traditional fishing practices.

In our tour of the area, Adolph took us on a walk through the remains of their ancient village at Keatley Creek, where my ancestors first built their winter homes between 4,800 and 2,400 years ago. Multiple round depressions appeared before us, spread out across a clearing in the land and looking like some kind of alien spaceship landing site. He explained we were looking at all that was left from prehistoric underground houses that St’át’imc families had made by digging out earth and supporting the walls and roof with angled wooden poles covered with woven mats and earth. They crafted wooden ladders for men to use to enter and exit from the smoke hole on top and for women to use from an entrance on the side. Families used these homes generation after generation. Today, these underground dwellings are called “pit houses;” however, in my mother’s St’át’imc language they are called “s7ístken” (pronounced she-ish-t-ken). It must have been challenging cooking, eating, sleeping and living partially underground for months at a time, sheltered from the wind and snow. Spring must have really been a time of excitement and celebration, when they could travel for seasonal hunting and salmon fishing and live above ground in mat-covered shelters.

Mom never told me about the early history of her people because she probably didn’t know it, but those were her people, which makes them my people. All of this makes for interesting thoughts now as I buy salmon at my local grocery store and cook it for dinner, wondering where it came from, while looking through the window to see the grass in my backyard in Toronto and wondering what it will look like 4,800 years from now.

Order now

from Amazon.ca or Chapters.Indigo.ca or contact your favourite bookseller or educational wholesaler