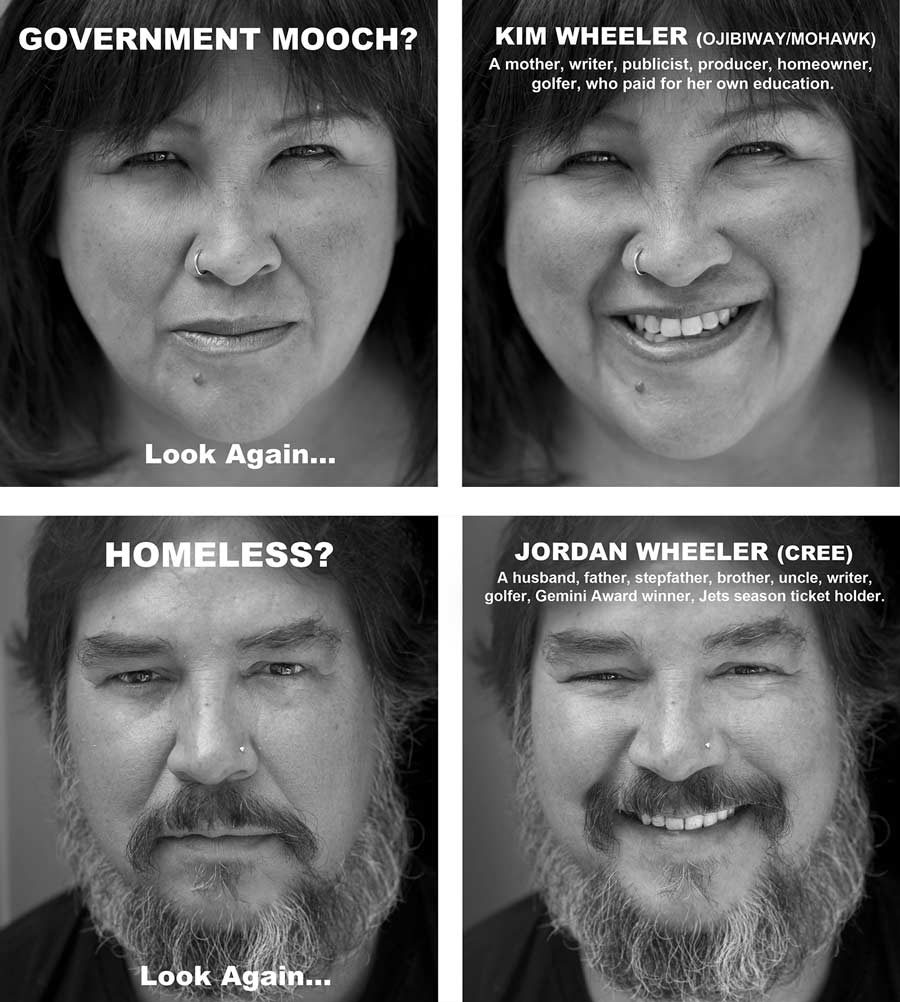

Racism

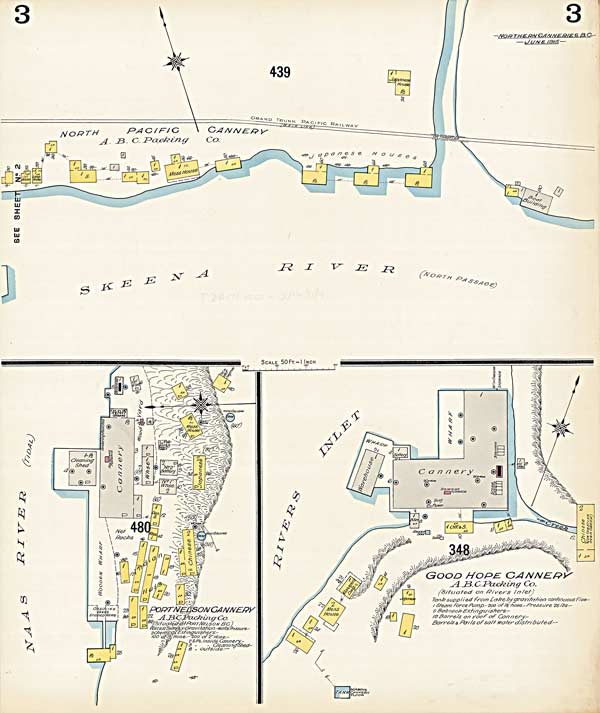

I am of Tsimshian and Japanese ancestry and spent my first 11 years living in a fishing-cannery town located in Tsimshian territory in northwest British Columbia. Our small community was divided into four distinct groups: the “village” (First Nations families from other Nations and territories); “cannery management” (predominantly European); “Asian” (Japanese and Chinese fishermen and cannery workers); and, lastly, “other” (including my family, which did not fit easily into a distinct category). The stark difference between these groups was highlighted by the types of housing they lived in and levels of income. In the “village,” families lived in small, cramped row houses with no bathrooms, often with five or more people sharing one or two rooms, while members of the other groups had larger houses equipped with flush toilets. This segregation was a constant reminder to my young mind of the importance people placed on difference.

The stark difference between these groups was highlighted by the types of housing they lived in and levels of income.

I learned at a young age that being different was not something to aspire to. People were often disliked, disrespected, teased, taunted or shunned simply because of difference. I remember fights over difference that included name calling, rock throwing and threats of, “Better watch it or I’m gonna beat you up!” I knew I was different and didn’t want to be beaten up, so I tried to fit in by joining in the name calling. I believed that my actions would prove my worth and my desire to belong would therefore be satisfied. Yet when all was calm again, I would feel further isolated for having chosen a side. I realized that in me lived a constant battle between who I was and who I wanted to be. I wanted to be who I wasn’t.

My cannery experience was over 40 years ago. While I now feel a greater sense of pride in my mixed ancestry, it still requires constant effort to overcome my childhood insecurities. I tend to approach unfamiliar or potentially uncomfortable situations with caution, and choose my words carefully in any conversation. This can be a positive attribute, and I can see how my early experiences have contributed to my ability to gauge tone, voice and body language. I take time to observe, analyze and assess dialogue before I engage. However, this way of interacting with the world becomes a challenge when I feel threatened, whether it be physically, mentally, spiritually or emotionally. Threats to my well-being quickly deplete my energy to the point that I become frozen and unable to act.

One of these moments occurred a while back when, after a hectic work week, a quiet dinner out with my husband was interrupted by the painful reality of racism. I could hear a small group of white men discussing “Indians.” The discussion seemed to be over federal fishing policies and quickly escalated into a bitter dialogue about Indigenous people. As the harsh opinions filled the air, I sat shocked and gently pulled my husband’s attention away from his phone, asking quietly, “Do you hear the conversation at the next table?”

One of the men asked, “What the hell is the rule about who is or isn’t Indian — one-quarter blood quantum — how in the hell do you prove that?” Their talk continued, ridiculing our inherent appreciation and value of the land, animals and environment, mockingly declaring, “They protest everything — oil, gas, land, water — everything!” The men ridiculed the validity of the education system, saying, “Our tax dollars are paying for the handful of Indians who actually made it through law school and are now suing the ass off our governments — what do they know?” One of the group exaggerated the number of land claims cases with, “There is a new Goddamn case in the courts every day!” And, one proclaimed, “Can you imagine — the Indians in the river fishing with grocery carts — grocery carts of all things, what a f***ing joke!” There was hardly a pause between each opinion and the expressions of approval from the others at their table. I was afraid to scan the room to see who else might be within earshot and listening.

With every statement, I fought the desire to retract into myself like a turtle into its shell. Internal conflict over what, and what not, to do caused my heart to race and my stomach to ache. I was aware of wanting to act, but feeling completely frozen. I recognize now the genesis of that struggle — the fear of having someone from this group direct their vitriol directly at me, because they saw my First Nations heritage, had me frozen in this vortex of hurt and guilt. The stark reminder of how I felt as a child who struggled to find a place of belonging was, and still is, as painful as the guilt I felt for momentarily losing my sense of pride in who I am. I sat motionless, silent, my eyes burning as I fought back tears. My inability to challenge the bigots at the nearby table was at odds with what I wished I could do. My mind said, “Seize the opportunity to educate — eliminate the ignorance,” while my heart said, “Protect your mind, body and spirit.” I chose my heart over my head because I felt that I needed to care for me first and foremost.

I wonder how I would have felt if I had confronted the racists. Maybe it would have helped me in ways I don’t yet know. Maybe not. But as I reflect on that incident, I know I can find a way to process these types of experiences through the work I do. Maybe I couldn’t challenge those men that day, but today I can share my stories (this one and others) when I talk with the adult students I work with about the importance of embracing who we are and the strengths we bring to this world. I can make real the words of my mother, a Tsimshian woman, who always said, “It’s not about fitting in or being someone that you are not — be proud of who you are and where you come from.”

I am no longer that child who was so afraid of being different. I am proud of who I am.

Order now

from Amazon.ca or Chapters.Indigo.ca or contact your favourite bookseller or educational wholesaler