Truth and Reconciliation

Contents

Other Sections

Introduction

There are two primary perspectives on the

country we call Canada — the perspectives of Indigenous Peoples and the perspectives of the tens of millions of people from different backgrounds who have come to this country to find a new home. While there is great diversity among Indigenous perspectives, one fact remains central — the traditional lands, practices, values, cultures, languages, systems and understandings of Indigenous Peoples have been systematically attacked, dismantled and destroyed at the hands of the Canadian state.

In 2008, following mass litigation and the outcry of Survivors of the residential schools for justice and healing, Canada launched the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. This Commission was intended not only to bring the voices of Survivors forward, but to fundamentally shift the national narrative away from a culture of domination and oppression and towards a culture of respect, reciprocity and understanding.

To be certain, Indigenous Peoples expected this relationship of equal partnership from the earliest days of encounter with newcomers. Treaties were signed in a spirit and intent of mutual respect and reciprocity. Ceremonies were held affirming this relationship. In areas where treaties were not signed, the expectation was for the self-determination and autonomy that had existed for millennia to continue.

It is through this resistance and the enhancement and rekindling of traditional practices, knowledges and Indigenous rights frameworks that Canada has the opportunity to become the nation that it has always been…

As the state encroached further and further into all aspects of Indigenous people’s lives, resistance to the aggressive assimilation policies of Canada was a constant across Indigenous communities, nations and peoples. Elders took ceremonies underground, families fought desperately to retain their languages, and communities created formal political, social, and economic structures aimed at resisting ongoing attempts to eradicate Indigenous Peoples and perspectives from Canada.

As a nation, the opportunity for Canada now is to celebrate and acknowledge the critical role of ongoing resistance. It is through this resistance and the enhancement and rekindling of traditional practices, knowledges and Indigenous rights frameworks that Canada has the opportunity to become the nation that it has always been — a nation of many rich traditions, identities and systems coming together to find solutions to many of the deep-seated social tensions and challenges we face as a collective society.

Reconciliation in this regard means arresting the attacks on Indigenous ways of knowing and being, and working from this day forward in a spirit of mutual respect and understanding.

The section of this atlas focused on residential schools covers some of the most devastating elements of Canada’s aggressive assimilation policies. Through these residential schools, Inuit, First Nations and Métis children were forcibly removed from their families and forced to adopt identities and practices not their own. When children resisted, they were punished and abused. All manner of physical, spiritual, emotional and sexual violence was rampant.

Similarly, through racist doctrines such as the Indian Act, parents were prevented from seeing their children, prevented from keeping their children at home with them, and barred from assembling and retaining legal counsel. The umbrella of oppression was expansive, complete and all-encompassing.

But this atlas is more than just a story of the residential schools; it also documents Canada’s current state of reconciliation. Across this country, untold numbers of children wait in unmarked cemeteries to be remembered and honoured. As some former residential school sites crumble, the vast majority have already been destroyed or lost to the erosion of history.

Canada’s journey towards equality, respect and justice is measured by the wide gaps that exist between the health and well-being of Indigenous Peoples and the protection of Indigenous rights, places, spaces and cultural memory.

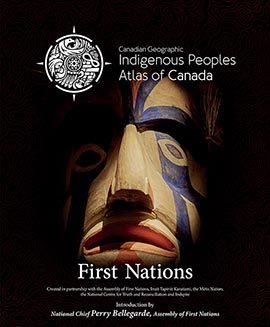

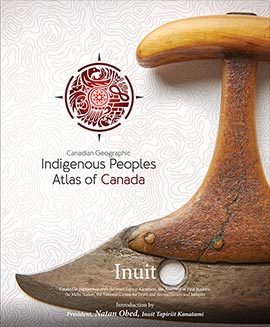

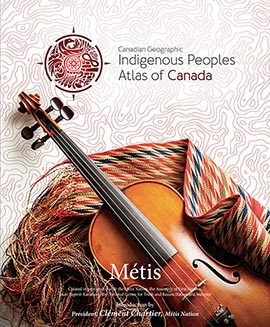

The other volumes in this atlas series point us collectively in a new direction — a direction that portrays a much more honest and accurate telling of history, and an unfolding of the land, cultures, and identities that existed before western powers drew lines on maps and divided families and communities from one another.

The surfacing of these long-standing understandings of this land is an essential part of creating a new national narrative. It pulls us away from the narrow definition of what it means to be Canadian and points us towards a new framework of understanding — one that acknowledges territory and the long and rich histories of Indigenous Peoples. It pushes us towards a concept of a nation with multiple forms of sovereignty existing within its borders — a place of respect wherein the unique political and social aspirations of Indigenous and non-Indigenous Peoples come together with a sense of common vision and destiny for a healthier, just, and sustainable society.

These volumes will help educate young Canadians for generations to come on what it means to be Canadian — what it means to be accountable to the original promises of treaty and what it means to honour the concept of unceded land. Moreover, they will give all

Canadians an opportunity to reflect further on what it means to take responsibility for successive governments’ persistent and omnipresent attempts to eradicate the meaning and context contained within Indigenous places and spaces from this country.

Canada’s journey towards equality, respect and justice is measured by the wide gaps that exist between the health and well-being of Indigenous Peoples…

The harm inflicted upon Indigenous Peoples is not only a problem for Indigenous Peoples. It is a Canadian problem that requires all Canadians to take responsibility and action to repair the damage done. Former TRC commissioner Wilton Littlechild recently talked about the opportunity presented to us as a whole, stating: “If two people are trying to walk down a railroad track, each balancing on a rail independently, they will not get very far. But if they join hands and walk together they will make it much further down the road.”

This is our opportunity — to walk side by side — Indigenous Peoples and non-Indigenous Peoples walking together towards the destination of a fair, equitable and just country. Gone must be the days where Indigenous Peoples are led down the track by those who know “what’s best for them.” These atlases equip all Canadians with an important set of tools to realize this goal. I hope you learn much from the materials contained within. Together, if we are willing, we can transform this country into something that we are all proud to call home.